このコンテンツは選択した言語では利用できません。

Creating Images

OpenShift Container Platform 3.4 Image Creation Guide

Abstract

Chapter 1. Overview

This guide provides best practices on writing and testing container images that can be used on OpenShift Container Platform. Once you have created an image, you can push it to the internal registry.

Chapter 2. Guidelines

2.1. Overview

When creating container images to run on OpenShift Container Platform there are a number of best practices to consider as an image author to ensure a good experience for consumers of those images. Because images are intended to be immutable and used as-is, the following guidelines help ensure that your images are highly consumable and easy to use on OpenShift Container Platform.

2.2. General Container Image Guidelines

The following guidelines apply when creating a container image in general, and are independent of whether the images are used on OpenShift Container Platform.

Reuse Images

Wherever possible, we recommend that you base your image on an appropriate upstream image using the FROM statement. This ensures your image can easily pick up security fixes from an upstream image when it is updated, rather than you having to update your dependencies directly.

In addition, use tags in the FROM instruction (for example, rhel:rhel7) to make it clear to users exactly which version of an image your image is based on. Using a tag other than latest ensures your image is not subjected to breaking changes that might go into the latest version of an upstream image.

Maintain Compatibility Within Tags

When tagging your own images, we recommend that you try to maintain backwards compatibility within a tag. For example, if you provide an image named foo and it currently includes version 1.0, you might provide a tag of foo:v1. When you update the image, as long as it continues to be compatible with the original image, you can continue to tag the new image foo:v1, and downstream consumers of this tag will be able to get updates without being broken.

If you later release an incompatible update, then you should switch to a new tag, for example foo:v2. This allows downstream consumers to move up to the new version at will, but not be inadvertently broken by the new incompatible image. Any downstream consumer using foo:latest takes on the risk of any incompatible changes being introduced.

Avoid Multiple Processes

We recommend that you do not start multiple services, such as a database and SSHD, inside one container. This is not necessary because containers are lightweight and can be easily linked together for orchestrating multiple processes. OpenShift Container Platform allows you to easily colocate and co-manage related images by grouping them into a single pod.

This collocation ensures the containers share a network namespace and storage for communication. Updates are also less disruptive as each image can be updated less frequently and independently. Signal handling flows are also clearer with a single process as you do not need to manage routing signals to spawned processes.

Use exec in Wrapper Scripts

See the "Always exec in Wrapper Scripts" section of the Project Atomic documentation for more information.

Also note that your process runs as PID 1 when running in a container. This means that if your main process terminates, the entire container is stopped, killing any child processes you may have launched from your PID 1 process.

See the "Docker and the PID 1 zombie reaping problem" blog article for additional implications. Also see the "Demystifying the init system (PID 1)" blog article for a deep dive on PID 1 and init systems.

Clean Temporary Files

All temporary files you create during the build process should be removed. This also includes any files added with the ADD command. For example, we strongly recommended that you run the yum clean command after performing yum install operations.

You can prevent the yum cache from ending up in an image layer by creating your RUN statement as follows:

RUN yum -y install mypackage && yum -y install myotherpackage && yum clean all -y

RUN yum -y install mypackage && yum -y install myotherpackage && yum clean all -yNote that if you instead write:

RUN yum -y install mypackage RUN yum -y install myotherpackage && yum clean all -y

RUN yum -y install mypackage

RUN yum -y install myotherpackage && yum clean all -y

Then the first yum invocation leaves extra files in that layer, and these files cannot be removed when the yum clean operation is run later. The extra files are not visible in the final image, but they are present in the underlying layers.

The current Docker build process does not allow a command run in a later layer to shrink the space used by the image when something was removed in an earlier layer. However, this may change in the future. This means that if you perform an rm command in a later layer, although the files are hidden it does not reduce the overall size of the image to be downloaded. Therefore, as with the yum clean example, it is best to remove files in the same command that created them, where possible, so they do not end up written to a layer.

In addition, performing multiple commands in a single RUN statement reduces the number of layers in your image, which improves download and extraction time.

Place Instructions in the Proper Order

Docker reads the Dockerfile and runs the instructions from top to bottom. Every instruction that is successfully executed creates a layer which can be reused the next time this or another image is built. It is very important to place instructions that will rarely change at the top of your Dockerfile. Doing so ensures the next builds of the same image are very fast because the cache is not invalidated by upper layer changes.

For example, if you are working on a Dockerfile that contains an ADD command to install a file you are iterating on, and a RUN command to yum install a package, it is best to put the ADD command last:

FROM foo RUN yum -y install mypackage && yum clean all -y ADD myfile /test/myfile

FROM foo

RUN yum -y install mypackage && yum clean all -y

ADD myfile /test/myfile

This way each time you edit myfile and rerun docker build, the system reuses the cached layer for the yum command and only generates the new layer for the ADD operation.

If instead you wrote the Dockerfile as:

FROM foo ADD myfile /test/myfile RUN yum -y install mypackage && yum clean all -y

FROM foo

ADD myfile /test/myfile

RUN yum -y install mypackage && yum clean all -y

Then each time you changed myfile and reran docker build, the ADD operation would invalidate the RUN layer cache, so the yum operation would need to be rerun as well.

Mark Important Ports

See the "Always EXPOSE Important Ports" section of the Project Atomic documentation for more information.

Set Environment Variables

It is good practice to set environment variables with the ENV instruction. One example is to set the version of your project. This makes it easy for people to find the version without looking at the Dockerfile. Another example is advertising a path on the system that could be used by another process, such as JAVA_HOME.

Avoid Default Passwords

It is best to avoid setting default passwords. Many people will extend the image and forget to remove or change the default password. This can lead to security issues if a user in production is assigned a well-known password. Passwords should be configurable using an environment variable instead. See the Using Environment Variables for Configuration topic for more information.

If you do choose to set a default password, ensure that an appropriate warning message is displayed when the container is started. The message should inform the user of the value of the default password and explain how to change it, such as what environment variable to set.

Avoid SSHD

It is best to avoid running SSHD in your image. You can use the docker exec command to access containers that are running on the local host. Alternatively, you can use the oc exec command or the oc rsh command to access containers that are running on the OpenShift Container Platform cluster. Installing and running SSHD in your image opens up additional vectors for attack and requirements for security patching.

Use Volumes for Persistent Data

Images should use a Docker volume for persistent data. This way OpenShift Container Platform mounts the network storage to the node running the container, and if the container moves to a new node the storage is reattached to that node. By using the volume for all persistent storage needs, the content is preserved even if the container is restarted or moved. If your image writes data to arbitrary locations within the container, that content might not be preserved.

All data that needs to be preserved even after the container is destroyed must be written to a volume. With Docker 1.5, there will be a readonly flag for containers which can be used to strictly enforce good practices about not writing data to ephemeral storage in a container. Designing your image around that capability now will make it easier to take advantage of it later.

Furthermore, explicitly defining volumes in your Dockerfile makes it easy for consumers of the image to understand what volumes they need to define when running your image.

See the Kubernetes documentation for more information on how volumes are used in OpenShift Container Platform.

Even with persistent volumes, each instance of your image has its own volume, and the filesystem is not shared between instances. This means the volume cannot be used to share state in a cluster.

External Guidelines

See the following references for other guidelines:

- Docker documentation - Best practices for writing Dockerfiles

- Project Atomic documentation - Guidance for Container Image Authors

2.3. OpenShift Container Platform-Specific Guidelines

The following are guidelines that apply when creating container images specifically for use on OpenShift Container Platform.

Enable Images for Source-To-Image (S2I)

For images that are intended to run application code provided by a third party, such as a Ruby image designed to run Ruby code provided by a developer, you can enable your image to work with the Source-to-Image (S2I) build tool. S2I is a framework which makes it easy to write images that take application source code as an input and produce a new image that runs the assembled application as output.

For example, this Python image defines S2I scripts for building various versions of Python applications.

For more details about how to write S2I scripts for your image, see the S2I Requirements topic.

Support Arbitrary User IDs

By default, OpenShift Container Platform runs containers using an arbitrarily assigned user ID. This provides additional security against processes escaping the container due to a container engine vulnerability and thereby achieving escalated permissions on the host node.

For an image to support running as an arbitrary user, directories and files that may be written to by processes in the image should be owned by the root group and be read/writable by that group. Files to be executed should also have group execute permissions.

Adding the following to your Dockerfile sets the directory and file permissions to allow users in the root group to access them in the built image:

RUN chgrp -R 0 /some/directory && \

chmod -R g=u /some/directory

RUN chgrp -R 0 /some/directory && \

chmod -R g=u /some/directoryBecause the container user is always a member of the root group, the container user can read and write these files. The root group does not have any special permissions (unlike the root user) so there are no security concerns with this arrangement. In addition, the processes running in the container must not listen on privileged ports (ports below 1024), since they are not running as a privileged user.

Because the user ID of the container is generated dynamically, it will not have an associated entry in /etc/passwd. This can cause problems for applications that expect to be able to look up their user ID. One way to address this problem is to dynamically create a passwd file entry with the container’s user ID as part of the image’s start script. This is what a Dockerfile might include:

RUN chmod g=u /etc/passwd ENTRYPOINT [ "uid_entrypoint" ] USER 1001

RUN chmod g=u /etc/passwd

ENTRYPOINT [ "uid_entrypoint" ]

USER 1001Where uid_entrypoint contains:

if ! whoami &> /dev/null; then

if [ -w /etc/passwd ]; then

echo "${USER_NAME:-default}:x:$(id -u):0:${USER_NAME:-default} user:${HOME}:/sbin/nologin" >> /etc/passwd

fi

fi

if ! whoami &> /dev/null; then

if [ -w /etc/passwd ]; then

echo "${USER_NAME:-default}:x:$(id -u):0:${USER_NAME:-default} user:${HOME}:/sbin/nologin" >> /etc/passwd

fi

fiFor a complete example of this, see this Dockerfile.

Lastly, the final USER declaration in the Dockerfile should specify the user ID (numeric value) and not the user name. This allows OpenShift Container Platform to validate the authority the image is attempting to run with and prevent running images that are trying to run as root, because running containers as a privileged user exposes potential security holes. If the image does not specify a USER, it inherits the USER from the parent image.

If your S2I image does not include a USER declaration with a numeric user, your builds will fail by default. In order to allow images that use either named users or the root (0) user to build in OpenShift Container Platform, you can add the project’s builder service account (system:serviceaccount:<your-project>:builder) to the privileged security context constraint (SCC). Alternatively, you can allow all images to run as any user.

Use Services for Inter-image Communication

For cases where your image needs to communicate with a service provided by another image, such as a web front end image that needs to access a database image to store and retrieve data, your image should consume an OpenShift Container Platform service. Services provide a static endpoint for access which does not change as containers are stopped, started, or moved. In addition, services provide load balancing for requests.

Provide Common Libraries

For images that are intended to run application code provided by a third party, ensure that your image contains commonly used libraries for your platform. In particular, provide database drivers for common databases used with your platform. For example, provide JDBC drivers for MySQL and PostgreSQL if you are creating a Java framework image. Doing so prevents the need for common dependencies to be downloaded during application assembly time, speeding up application image builds. It also simplifies the work required by application developers to ensure all of their dependencies are met.

Use Environment Variables for Configuration

Users of your image should be able to configure it without having to create a downstream image based on your image. This means that the runtime configuration should be handled using environment variables. For a simple configuration, the running process can consume the environment variables directly. For a more complicated configuration or for runtimes which do not support this, configure the runtime by defining a template configuration file that is processed during startup. During this processing, values supplied using environment variables can be substituted into the configuration file or used to make decisions about what options to set in the configuration file.

It is also possible and recommended to pass secrets such as certificates and keys into the container using environment variables. This ensures that the secret values do not end up committed in an image and leaked into a Docker registry.

Providing environment variables allows consumers of your image to customize behavior, such as database settings, passwords, and performance tuning, without having to introduce a new layer on top of your image. Instead, they can simply define environment variable values when defining a pod and change those settings without rebuilding the image.

For extremely complex scenarios, configuration can also be supplied using volumes that would be mounted into the container at runtime. However, if you elect to do it this way you must ensure that your image provides clear error messages on startup when the necessary volume or configuration is not present.

This topic is related to the Using Services for Inter-image Communication topic in that configuration like datasources should be defined in terms of environment variables that provide the service endpoint information. This allows an application to dynamically consume a datasource service that is defined in the OpenShift Container Platform environment without modifying the application image.

In addition, tuning should be done by inspecting the cgroups settings for the container. This allows the image to tune itself to the available memory, CPU, and other resources. For example, Java-based images should tune their heap based on the cgroup maximum memory parameter to ensure they do not exceed the limits and get an out-of-memory error.

See the following references for more on how to manage cgroup quotas in Docker containers:

- Blog article - Resource management in Docker

- Docker documentation - Runtime Metrics

- Blog article - Memory inside Linux containers

Set Image Metadata

Defining image metadata helps OpenShift Container Platform better consume your container images, allowing OpenShift Container Platform to create a better experience for developers using your image. For example, you can add metadata to provide helpful descriptions of your image, or offer suggestions on other images that may also be needed.

See the Image Metadata topic for more information on supported metadata and how to define them.

Clustering

You must fully understand what it means to run multiple instances of your image. In the simplest case, the load balancing function of a service handles routing traffic to all instances of your image. However, many frameworks need to share information in order to perform leader election or failover state; for example, in session replication.

Consider how your instances accomplish this communication when running in OpenShift Container Platform. Although pods can communicate directly with each other, their IP addresses change anytime the pod starts, stops, or is moved. Therefore, it is important for your clustering scheme to be dynamic.

Logging

It is best to send all logging to standard out. OpenShift Container Platform collects standard out from containers and sends it to the centralized logging service where it can be viewed. If you need to separate log content, prefix the output with an appropriate keyword, which makes it possible to filter the messages.

If your image logs to a file, users must use manual operations to enter the running container and retrieve or view the log file.

Liveness and Readiness Probes

Document example liveness and readiness probes that can be used with your image. These probes will allow users to deploy your image with confidence that traffic will not be routed to the container until it is prepared to handle it, and that the container will be restarted if the process gets into an unhealthy state.

Templates

Consider providing an example template with your image. A template will give users an easy way to quickly get your image deployed with a working configuration. Your template should include the liveness and readiness probes you documented with the image, for completeness.

2.4. External References

Chapter 3. Image Metadata

3.1. Overview

Defining image metadata helps OpenShift Container Platform better consume your container images, allowing OpenShift Container Platform to create a better experience for developers using your image. For example, you can add metadata to provide helpful descriptions of your image, or offer suggestions on other images that may also be needed.

This topic only defines the metadata needed by the current set of use cases. Additional metadata or use cases may be added in the future.

3.2. Defining Image Metadata

You can use the LABEL instruction in a Dockerfile to define image metadata. Labels are similar to environment variables in that they are key value pairs attached to an image or a container. Labels are different from environment variable in that they are not visible to the running application and they can also be used for fast look-up of images and containers.

Docker documentation for more information on the LABEL instruction.

The label names should typically be namespaced. The namespace should be set accordingly to reflect the project that is going to pick up the labels and use them. For OpenShift Container Platform the namespace should be set to io.openshift and for Kubernetes the namespace is io.k8s.

See the Docker custom metadata documentation for details about the format.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

|

| This label contains a list of tags represented as list of comma separated string values. The tags are the way to categorize the container images into broad areas of functionality. Tags help UI and generation tools to suggest relevant container images during the application creation process. LABEL io.openshift.tags mongodb,mongodb24,nosql |

|

|

Specifies a list of tags that the generation tools and the UI might use to provide relevant suggestions if you don’t have the container images with given tags already. For example, if the container image wants LABEL io.openshift.wants mongodb,redis |

|

| This label can be used to give the container image consumers more detailed information about the service or functionality this image provides. The UI can then use this description together with the container image name to provide more human friendly information to end users. LABEL io.k8s.description The MySQL 5.5 Server with master-slave replication support |

|

|

An image might use this variable to suggest that it does not support scaling. The UI will then communicate this to consumers of that image. Being not-scalable basically means that the value of LABEL io.openshift.non-scalable true |

|

| This label suggests how much resources the container image might need in order to work properly. The UI might warn the user that deploying this container image may exceed their user quota. The values must be compatible with Kubernetes quantity. LABEL io.openshift.min-memory 8Gi LABEL io.openshift.min-cpu 4 |

Chapter 4. S2I Requirements

4.1. Overview

Source-to-Image (S2I) is a framework that makes it easy to write images that take application source code as an input and produce a new image that runs the assembled application as output.

The main advantage of using S2I for building reproducible container images is the ease of use for developers. As a builder image author, you must understand two basic concepts in order for your images to provide the best possible S2I performance: the build process and S2I scripts.

4.2. Build Process

The build process consists of the following three fundamental elements, which are combined into a final container image:

- sources

- S2I scripts

- builder image

During the build process, S2I must place sources and scripts inside the builder image. To do so, S2I creates a tar file that contains the sources and scripts, then streams that file into the builder image. Before executing the assemble script, S2I untars that file and places its contents into the location specified by the io.openshift.s2i.destination label from the builder image, with the default location being the /tmp directory.

For this process to happen, your image must supply the tar archiving utility (the tar command available in $PATH) and the command line interpreter (the /bin/sh command); this allows your image to use the fastest possible build path. If the tar or /bin/sh command is not available, the s2i build process is forced to automatically perform an additional container build to put both the sources and the scripts inside the image, and only then run the usual build.

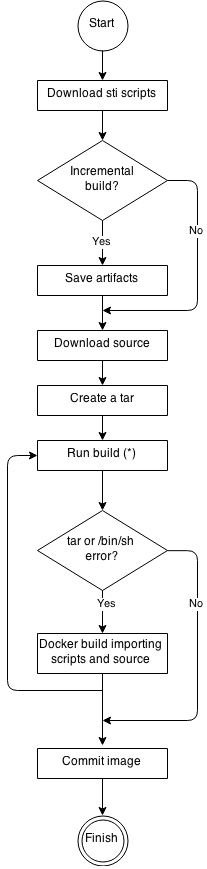

See the following diagram for the basic S2I build workflow:

Figure 4.1. Build Workflow

-

Run build’s responsibility is to untar the sources, scripts and artifacts (if such exist) and invoke the

assemblescript. If this is the second run (after catchingtaror/bin/shnot found error) it is responsible only for invokingassemblescript, since both scripts and sources are already there.

4.3. S2I Scripts

You can write S2I scripts in any programming language, as long as the scripts are executable inside the builder image. S2I supports multiple options providing assemble/run/save-artifacts scripts. All of these locations are checked on each build in the following order:

- A script specified in the BuildConfig

-

A script found in the application source

.s2i/bindirectory -

A script found at the default image URL (

io.openshift.s2i.scripts-urllabel)

Both the io.openshift.s2i.scripts-url label specified in the image and the script specified in a BuildConfig can take one of the following forms:

-

image:///path_to_scripts_dir- absolute path inside the image to a directory where the S2I scripts are located -

file:///path_to_scripts_dir- relative or absolute path to a directory on the host where the S2I scripts are located -

http(s)://path_to_scripts_dir- URL to a directory where the S2I scripts are located

| Script | Description |

|---|---|

| assemble (required) | The assemble script builds the application artifacts from a source and places them into appropriate directories inside the image. The workflow for this script is:

|

| run (required) | The run script executes your application. |

| save-artifacts (optional) | The save-artifacts script gathers all dependencies that can speed up the build processes that follow. For example:

These dependencies are gathered into a tar file and streamed to the standard output. |

| usage (optional) | The usage script allows you to inform the user how to properly use your image. |

| test/run (optional) | The test/run script allows you to create a simple process to check if the image is working correctly. The proposed flow of that process is:

See the Testing S2I Images topic for more information. Note The suggested location to put the test application built by your test/run script is the test/test-app directory in your image repository. See the S2I documentation for more information. |

Example S2I Scripts

The following examples are written in Bash and it is assumed all tar contents are unpacked into the /tmp/s2i directory.

Example 4.1. assemble script:

Example 4.2. run script:

#!/bin/bash run the application /opt/application/run.sh

#!/bin/bash

# run the application

/opt/application/run.shExample 4.3. save-artifacts script:

Example 4.4. usage script:

4.4. Using Images with ONBUILD Instructions

The ONBUILD instructions can be found in many official Docker images. For example:

See the Docker documentation for more information on ONBUILD.

Upon startup, S2I detects whether the builder image contains sh and tar binaries which are necessary for the S2I process to inject build inputs. If the builder image does not contain these prerequisites, it will attempt to instead perform a container build to layer the inputs. If the builder image includes ONBUILD instructions, S2I will instead fail the build because the ONBUILD instructions would be executed during the layering process, and that equates to performing a generic container build which is less secure than an S2I build and requires explicit permissions.

Therefore you should ensure that your S2I builder image either does not contain ONBUILD instructions, or ensure that it has the necessary sh and tar binary prerequisites.

4.5. External References

Chapter 5. Testing S2I Images

5.1. Overview

As an Source-to-Image (S2I) builder image author, you can test your S2I image locally and use the OpenShift Container Platform build system for automated testing and continuous integration.

Check the S2I Requirements topic to learn more about the S2I architecture before proceeding.

As described in the S2I Requirements topic, S2I requires the assemble and run scripts to be present in order to successfully execute the S2I build. Providing the save-artifacts script reuses the build artifacts, and providing the usage script ensures that usage information is printed to console when someone runs the container image outside of the S2I.

The goal of testing an S2I image is to make sure that all of these described commands work properly, even if the base container image has changed or the tooling used by the commands was updated.

5.2. Testing Requirements

The standard location for the test script is test/run. This script is invoked by the OpenShift Container Platform S2I image builder and it could be a simple Bash script or a static Go binary.

The test/run script performs the S2I build, so you must have the S2I binary available in your $PATH. If required, follow the installation instructions in the S2I README.

S2I combines the application source code and builder image, so in order to test it you need a sample application source to verify that the source successfully transforms into a runnable container image. The sample application should be simple, but it should exercise the crucial steps of assemble and run scripts.

5.3. Generating Scripts and Tools

The S2I tooling comes with powerful generation tools to speed up the process of creating a new S2I image. The s2i create command produces all the necessary S2I scripts and testing tools along with the Makefile:

The generated test/run script must be adjusted to be useful, but it provides a good starting point to begin developing.

The test/run script produced by the s2i create command requires that the sample application sources are inside the test/test-app directory.

5.4. Testing Locally

The easiest way to run the S2I image tests locally is to use the generated Makefile.

If you did not use the s2i create command, you can copy the following Makefile template and replace the IMAGE_NAME parameter with your image name.

Example 5.1. Sample Makefile

5.5. Basic Testing Workflow

The test script assumes you have already built the image you want to test. If required, first build the S2I image using:

The following steps describe the default workflow to test S2I image builders:

Verify the usage script is working:

Build the image:

- Optionally, if you support save-artifacts, execute step 2 once again to verify that saving and restoring artifacts works properly.

Run the container:

- Verify the container is running and the application is responding.

Executing these steps is generally enough to tell if the builder image is working as expected.

5.6. Using OpenShift Container Platform Build for Automated Testing

Another way you can execute the S2I image tests is to use the OpenShift Container Platform platform itself as a continuous integration system. The OpenShift Container Platform platform is capable of building container images and is highly customizable.

To set up an S2I image builder continuous integration system, define a Custom build and use the openshift/sti-image-builder image. This image executes all the steps mentioned in the Basic Testing Workflow section and creates a new S2I builder image.

Example 5.2. Sample CustomBuild

You can use the oc create command to create this BuildConfig. After you create the BuildConfig, you can start the build using the following command:

If your OpenShift Container Platform instance is hosted on a public IP address, the build can be triggered each time you push into your S2I builder image GitHub repository. See webhook triggers for more information.

You can also use the CustomBuild to trigger a rebuild of your application based on the S2I image you updated. See image change triggers for more information.

Chapter 6. Custom Builder

6.1. Overview

By allowing you to define a specific builder image responsible for the entire build process, OpenShift Container Platform’s Custom build strategy was designed to fill a gap created with the increased popularity of creating container images. When there is a requirement for a build to still produce individual artifacts (packages, JARs, WARs, installable ZIPs, and base images, for example), a Custom builder image using the Custom build strategy is the perfect match to fill that gap.

A Custom builder image is a plain container image embedded with build process logic, for example for building RPMs or base container images. The openshift/origin-custom-docker-builder image is available on the Docker Hub as an example implementation of a Custom builder image.

Additionally, the Custom builder allows implementing any extended build process, for example a CI/CD flow that runs unit or integration tests.

To fully leverage the benefits of the Custom build strategy, you must understand how to create a Custom builder image that will be capable of building desired objects.

6.2. Custom Builder Image

Upon invocation, a custom builder image will receive the following environment variables with the information needed to proceed with the build:

| Variable Name | Description |

|---|---|

|

|

The entire serialized JSON of the |

|

| The URL of a Git repository with source to be built. |

|

|

Uses the same value as |

|

| Specifies the subdirectory of the Git repository to be used when building. Only present if defined. |

|

| The Git reference to be built. |

|

| The version of the OpenShift Container Platform master that created this build object. |

|

| The Docker registry to push the image to. |

|

| The Docker tag name for the image being built. |

|

|

The path to the Docker credentials for running a |

|

|

Specifies the path to the Docker socket, if exposing the Docker socket was enabled in the build configuration (if |

It is recommended that you write your Custom builder image to only read the information provided by the BUILD environment variable, which conforms to an OpenShift Container Platform API version. You can then parse the required information from the build definition JSON instead of relying on the other individual environment variables provided to the builder image. However, the individual environment variables are provided for convenience if you do not want to parse the build definition.

6.3. Custom Builder Workflow

Although Custom builder image authors have great flexibility in defining the build process, your builder image must still adhere to the following required steps necessary for seamlessly running a build inside of OpenShift Container Platform:

-

Read the

Buildobject definition, which contains all the necessary information about input parameters for the build. - Run the build process.

- If your build produces an image, push it to the build’s output location if it is defined. Other output locations can be passed with environment variables.

Chapter 7. Revision History: Creating Images

7.1. Fri Feb 24 2017

| Affected Topic | Description of Change |

|---|---|

| Updated the commands in the Support Arbitrary User IDs section to enable root group access in the Dockerfile. |

7.2. Wed Jan 18 2017

OpenShift Container Platform 3.4 initial release.

Legal Notice

Copyright © Red Hat

OpenShift documentation is licensed under the Apache License 2.0 (https://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0).

Modified versions must remove all Red Hat trademarks.

Portions adapted from https://github.com/kubernetes-incubator/service-catalog/ with modifications by Red Hat.

Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Red Hat logo, the Shadowman logo, JBoss, OpenShift, Fedora, the Infinity logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries.

Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries.

Java® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates.

XFS® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries.

MySQL® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries.

Node.js® is an official trademark of the OpenJS Foundation.

The OpenStack® Word Mark and OpenStack logo are either registered trademarks/service marks or trademarks/service marks of the OpenStack Foundation, in the United States and other countries and are used with the OpenStack Foundation’s permission. We are not affiliated with, endorsed or sponsored by the OpenStack Foundation, or the OpenStack community.

All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners.