Logical Volume Manager Administration

LVM Administrator Guide

Abstract

Chapter 1. Introduction

1.1. Audience

1.2. Software Versions

| Software | Description |

|---|---|

|

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6

|

refers to Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 and higher

|

|

GFS2

|

refers to GFS2 for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 and higher

|

1.3. Related Documentation

- Installation Guide — Documents relevant information regarding the installation of Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.

- Deployment Guide — Documents relevant information regarding the deployment, configuration and administration of Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.

- Storage Administration Guide — Provides instructions on how to effectively manage storage devices and file systems on Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.

- High Availability Add-On Overview — Provides a high-level overview of the Red Hat High Availability Add-On.

- Cluster Administration — Provides information about installing, configuring and managing the Red Hat High Availability Add-On,

- Global File System 2: Configuration and Administration — Provides information about installing, configuring, and maintaining Red Hat GFS2 (Red Hat Global File System 2), which is included in the Resilient Storage Add-On.

- DM Multipath — Provides information about using the Device-Mapper Multipath feature of Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.

- Load Balancer Administration — Provides information on configuring high-performance systems and services with the Load Balancer Add-On, a set of integrated software components that provide Linux Virtual Servers (LVS) for balancing IP load across a set of real servers.

- Release Notes — Provides information about the current release of Red Hat products.

1.4. We Need Feedback!

Logical_Volume_Manager_Administration(EN)-6 (2017-3-8-15:20)

Logical_Volume_Manager_Administration(EN)-6 (2017-3-8-15:20)Chapter 2. The LVM Logical Volume Manager

2.1. New and Changed Features

2.1.1. New and Changed Features for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.0

- You can define how a mirrored logical volume behaves in the event of a device failure with the

mirror_image_fault_policyandmirror_log_fault_policyparameters in theactivationsection of thelvm.conffile. When this parameter is set toremove, the system attempts to remove the faulty device and run without it. When this parameter is set toallocate, the system attempts to remove the faulty device and tries to allocate space on a new device to be a replacement for the failed device; this policy acts like theremovepolicy if no suitable device and space can be allocated for the replacement. For information on the LVM mirror failure policies, see Section 5.4.3.1, “Mirrored Logical Volume Failure Policy”. - For the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 release, the Linux I/O stack has been enhanced to process vendor-provided I/O limit information. This allows storage management tools, including LVM, to optimize data placement and access. This support can be disabled by changing the default values of

data_alignment_detectionanddata_alignment_offset_detectionin thelvm.conffile, although disabling this support is not recommended.For information on data alignment in LVM as well as information on changing the default values ofdata_alignment_detectionanddata_alignment_offset_detection, see the inline documentation for the/etc/lvm/lvm.conffile, which is also documented in Appendix B, The LVM Configuration Files. For general information on support for the I/O Stack and I/O limits in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6, see the Storage Administration Guide. - In Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6, the Device Mapper provides direct support for

udevintegration. This synchronizes the Device Mapper with alludevprocessing related to Device Mapper devices, including LVM devices. For information on Device Mapper support for theudevdevice manager, see Section A.3, “Device Mapper Support for the udev Device Manager”. - For the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 release, you can use the

lvconvert --repaircommand to repair a mirror after disk failure. This brings the mirror back into a consistent state. For information on thelvconvert --repaircommand, see Section 5.4.3.3, “Repairing a Mirrored Logical Device”. - As of the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 release, you can use the

--mergeoption of thelvconvertcommand to merge a snapshot into its origin volume. For information on merging snapshots, see Section 5.4.8, “Merging Snapshot Volumes”. - As of the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 release, you can use the

--splitmirrorsargument of thelvconvertcommand to split off a redundant image of a mirrored logical volume to form a new logical volume. For information on using this option, see Section 5.4.3.2, “Splitting Off a Redundant Image of a Mirrored Logical Volume”. - You can now create a mirror log for a mirrored logical device that is itself mirrored by using the

--mirrorlog mirroredargument of thelvcreatecommand when creating a mirrored logical device. For information on using this option, see Section 5.4.3, “Creating Mirrored Volumes”.

2.1.2. New and Changed Features for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.1

- The Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.1 release supports the creation of snapshot logical volumes of mirrored logical volumes. You create a snapshot of a mirrored volume just as you would create a snapshot of a linear or striped logical volume. For information on creating snapshot volumes, see Section 5.4.5, “Creating Snapshot Volumes”.

- When extending an LVM volume, you can now use the

--alloc clingoption of thelvextendcommand to specify theclingallocation policy. This policy will choose space on the same physical volumes as the last segment of the existing logical volume. If there is insufficient space on the physical volumes and a list of tags is defined in thelvm.conffile, LVM will check whether any of the tags are attached to the physical volumes and seek to match those physical volume tags between existing extents and new extents.For information on extending LVM mirrored volumes with the--alloc clingoption of thelvextendcommand, see Section 5.4.14.3, “Extending a Logical Volume with theclingAllocation Policy”. - You can now specify multiple

--addtagand--deltagarguments within a singlepvchange,vgchange, orlvchangecommand. For information on adding and removing object tags, see Section D.1, “Adding and Removing Object Tags”. - The list of allowed characters in LVM object tags has been extended, and tags can contain the "/", "=", "!", ":", "#", and "&" characters. For information on LVM object tags, see Appendix D, LVM Object Tags.

- You can now combine RAID0 (striping) and RAID1 (mirroring) in a single logical volume. Creating a logical volume while simultaneously specifying the number of mirrors (

--mirrors X) and the number of stripes (--stripes Y) results in a mirror device whose constituent devices are striped. For information on creating mirrored logical volumes, see Section 5.4.3, “Creating Mirrored Volumes”. - As of the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.1 release, if you need to create a consistent backup of data on a clustered logical volume you can activate the volume exclusively and then create the snapshot. For information on activating logical volumes exclusively on one node, see Section 5.7, “Activating Logical Volumes on Individual Nodes in a Cluster”.

2.1.3. New and Changed Features for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.2

- The Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.2 release supports the

issue_discardsparameter in thelvm.confconfiguration file. When this parameter is set, LVM will issue discards to a logical volume's underlying physical volumes when the logical volume is no longer using the space on the physical volumes. For information on this parameter, see the inline documentation for the/etc/lvm/lvm.conffile, which is also documented in Appendix B, The LVM Configuration Files.

2.1.4. New and Changed Features for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.3

- As of the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.3 release, LVM supports RAID4/5/6 and a new implementation of mirroring. For information on RAID logical volumes, see Section 5.4.16, “RAID Logical Volumes”.

- When you are creating a new mirror that does not need to be revived, you can specify the

--nosyncargument to indicate that an initial synchronization from the first device is not required. For information on creating mirrored volumes, see Section 5.4.3, “Creating Mirrored Volumes”. - This manual now documents the snapshot

autoextendfeature. For information on creating snapshot volumes, see Section 5.4.5, “Creating Snapshot Volumes”.

2.1.5. New and Changed Features for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.4

- Logical volumes can now be thinly provisioned. This allows you to create logical volumes that are larger than the available extents. Using thin provisioning, you can manage a storage pool of free space, known as a thin pool, to be allocated to an arbitrary number of devices when needed by applications. You can then create devices that can be bound to the thin pool for later allocation when an application actually writes to the logical volume. The thin pool can be expanded dynamically when needed for cost-effective allocation of storage space.For general information on thinly-provisioned logical volumes, see Section 3.3.5, “Thinly-Provisioned Logical Volumes (Thin Volumes)”. For information on creating thin volumes, see Section 5.4.4, “Creating Thinly-Provisioned Logical Volumes”.

- The Red Hat Enterprise Linux release 6.4 version of LVM provides support for thinly-provisioned snapshot volumes. Thin snapshot volumes allow many virtual devices to be stored on the same data volume. This simplifies administration and allows for the sharing of data between snapshot volumes.For general information on thinly-provisioned snapshot volumes, see Section 3.3.7, “Thinly-Provisioned Snapshot Volumes”. For information on creating thin snapshot volumes, see Section 5.4.6, “Creating Thinly-Provisioned Snapshot Volumes”.

- This document includes a new section detailing LVM allocation policy, Section 5.3.2, “LVM Allocation”.

- LVM now provides support for

raid10logical volumes. For information on RAID logical volumes, see Section 5.4.16, “RAID Logical Volumes”. - The LVM metadata daemon,

lvmetad, is supported in Red Hat Enterprise Linux release 6.4. Enabling this daemon reduces the amount of scanning on systems with many block devices. Thelvmetaddaemon is not currently supported across the nodes of a cluster, and requires that the locking type be local file-based locking.For information on the metadata daemon, see Section 4.6, “The Metadata Daemon (lvmetad)”.

2.1.6. New and Changed Features for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.5

- You can control I/O operations on a RAID1 logical volume with the

--writemostlyand--writebehindparameters of thelvchangecommand. For information on these parameters, see Section 5.4.16.11, “Controlling I/O Operations on a RAID1 Logical Volume”. - The

lvchangecommand now supports a--refreshparameter that allows you to restore a transiently failed device without having to reactivate the device. This feature is described in Section 5.4.16.8.1, “The allocate RAID Fault Policy”. - LVM provides scrubbing support for RAID logical volumes. For information on this feature, see Section 5.4.16.10, “Scrubbing a RAID Logical Volume”.

- The fields that the

lvscommand supports have been updated. For information on thelvscommand, see Table 5.4, “lvs Display Fields”. - The

lvchangecommand supports the new--maxrecoveryrateand--minrecoveryrateparameters, which allow you to control the rate at whichsyncoperations are performed. For information on these parameters, see Section 5.4.16.10, “Scrubbing a RAID Logical Volume”. - You can control the rate at which a RAID logical volume is initialized by implementing recovery throttling. You control the rate at which

syncoperations are performed by setting the minimum and maximum I/O rate for those operations with the--minrecoveryrateand--maxrecoveryrateoptions of thelvcreatecommand, as described in Section 5.4.16.1, “Creating a RAID Logical Volume”. - You can now create a thinly-provisioned snapshot of a non-thinly-provisioned logical volume. For information on creating these volumes, known as external volumes, see Section 3.3.7, “Thinly-Provisioned Snapshot Volumes”.

2.1.7. New and Changed Features for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.6

- The documentation for thinly-provisioned volumes and thinly-provisioned snapshots has been clarified. Additional information about LVM thin provisioning is now provided in the

lvmthin(7) man page. For general information on thinly-provisioned logical volumes, see Section 3.3.5, “Thinly-Provisioned Logical Volumes (Thin Volumes)”. For information on thinly-provisioned snapshot volumes, see Section 3.3.7, “Thinly-Provisioned Snapshot Volumes”. - This manual now documents the

lvm dumpconfigcommand, in Section B.2, “ThelvmconfigCommand”. Note that as of the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.8 release, this command was renamedlvmconf, although the old format continues to work. - This manual now documents LVM profiles, in Section B.3, “LVM Profiles”.

- This manual now documents the

lvmcommand in Section 4.7, “Displaying LVM Information with thelvmCommand”. - In the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.6 release, you can control activation of thin pool snapshots with the -k and -K options of the

lvcreateandlvchangecommand, as documented in Section 5.4.17, “Controlling Logical Volume Activation”. - This manual documents the

--forceargument of thevgimportcommand. This allows you to import volume groups that are missing physical volumes and subsequently run thevgreduce --removemissingcommand. For information on thevgimportcommand, see Section 5.3.15, “Moving a Volume Group to Another System”.

2.1.8. New and Changed Features for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.7

- As of Red Hat Enterprise Linux release 6.7, many LVM processing commands accept the

-Sor--selectoption to define selection criteria for those commands. LVM selection criteria are documented in the new appendix Appendix C, LVM Selection Criteria. - This document provides basic procedures for creating cache logical volumes in Section 5.4.7, “Creating LVM Cache Logical Volumes”.

- The troubleshooting chapter of this document includes a new section, Section 7.8, “Duplicate PV Warnings for Multipathed Devices”.

2.1.9. New and Changed Features for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.8

- When defining selection criteria for LVM commands, you can now specify time values as selection criteria for fields with a field type of

time. For information on specifying time values as selection criteria, see Section C.3.1, “Specifying Time Values”.

2.2. Logical Volumes

- Flexible capacityWhen using logical volumes, file systems can extend across multiple disks, since you can aggregate disks and partitions into a single logical volume.

- Resizeable storage poolsYou can extend logical volumes or reduce logical volumes in size with simple software commands, without reformatting and repartitioning the underlying disk devices.

- Online data relocationTo deploy newer, faster, or more resilient storage subsystems, you can move data while your system is active. Data can be rearranged on disks while the disks are in use. For example, you can empty a hot-swappable disk before removing it.

- Convenient device namingLogical storage volumes can be managed in user-defined groups, which you can name according to your convenience.

- Disk stripingYou can create a logical volume that stripes data across two or more disks. This can dramatically increase throughput.

- Mirroring volumesLogical volumes provide a convenient way to configure a mirror for your data.

- Volume SnapshotsUsing logical volumes, you can take device snapshots for consistent backups or to test the effect of changes without affecting the real data.

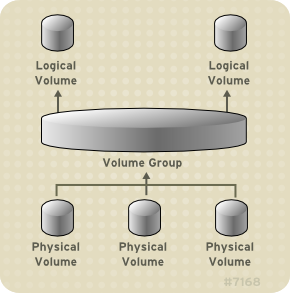

2.3. LVM Architecture Overview

- flexible capacity

- more efficient metadata storage

- better recovery format

- new ASCII metadata format

- atomic changes to metadata

- redundant copies of metadata

vgconvert command. For information on converting LVM metadata format, see the vgconvert(8) man page.

Figure 2.1. LVM Logical Volume Components

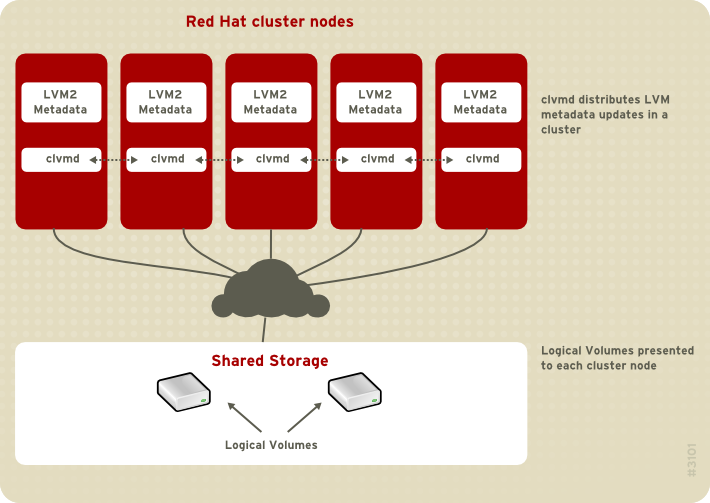

2.4. The Clustered Logical Volume Manager (CLVM)

- If only one node of your system requires access to the storage you are configuring as logical volumes, then you can use LVM without the CLVM extensions and the logical volumes created with that node are all local to the node.

- If you are using a clustered system for failover where only a single node that accesses the storage is active at any one time, you should use High Availability Logical Volume Management agents (HA-LVM).

- If more than one node of your cluster will require access to your storage which is then shared among the active nodes, then you must use CLVM. CLVM allows a user to configure logical volumes on shared storage by locking access to physical storage while a logical volume is being configured, and uses clustered locking services to manage the shared storage.

clvmd daemon, must be running. The clvmd daemon is the key clustering extension to LVM. The clvmd daemon runs in each cluster computer and distributes LVM metadata updates in a cluster, presenting each cluster computer with the same view of the logical volumes. For information on installing and administering the High Availability Add-On see Cluster Administration.

clvmd is started at boot time, you can execute a chkconfig ... on command on the clvmd service, as follows:

chkconfig clvmd on

# chkconfig clvmd onclvmd daemon has not been started, you can execute a service ... start command on the clvmd service, as follows:

service clvmd start

# service clvmd startWarning

Figure 2.2. CLVM Overview

Note

lvm.conf file for cluster-wide locking. Information on configuring the lvm.conf file to support clustered locking is provided within the lvm.conf file itself. For information about the lvm.conf file, see Appendix B, The LVM Configuration Files.

2.5. Document Overview

- Chapter 3, LVM Components describes the components that make up an LVM logical volume.

- Chapter 4, LVM Administration Overview provides an overview of the basic steps you perform to configure LVM logical volumes, whether you are using the LVM Command Line Interface (CLI) commands or the LVM Graphical User Interface (GUI).

- Chapter 5, LVM Administration with CLI Commands summarizes the individual administrative tasks you can perform with the LVM CLI commands to create and maintain logical volumes.

- Chapter 6, LVM Configuration Examples provides a variety of LVM configuration examples.

- Chapter 7, LVM Troubleshooting provides instructions for troubleshooting a variety of LVM issues.

- Chapter 8, LVM Administration with the LVM GUI summarizes the operating of the LVM GUI.

- Appendix A, The Device Mapper describes the Device Mapper that LVM uses to map logical and physical volumes.

- Appendix B, The LVM Configuration Files describes the LVM configuration files.

- Appendix D, LVM Object Tags describes LVM object tags and host tags.

- Appendix E, LVM Volume Group Metadata describes LVM volume group metadata, and includes a sample copy of metadata for an LVM volume group.

Chapter 3. LVM Components

3.1. Physical Volumes

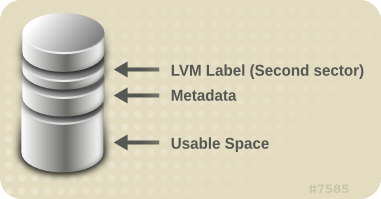

3.1.1. LVM Physical Volume Layout

Note

Figure 3.1. Physical Volume layout

3.1.2. Multiple Partitions on a Disk

- Administrative convenienceIt is easier to keep track of the hardware in a system if each real disk only appears once. This becomes particularly true if a disk fails. In addition, multiple physical volumes on a single disk may cause a kernel warning about unknown partition types at boot-up.

- Striping performanceLVM cannot tell that two physical volumes are on the same physical disk. If you create a striped logical volume when two physical volumes are on the same physical disk, the stripes could be on different partitions on the same disk. This would result in a decrease in performance rather than an increase.

3.2. Volume Groups

3.3. LVM Logical Volumes

3.3.1. Linear Volumes

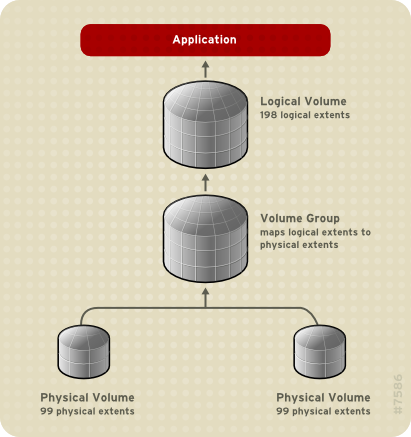

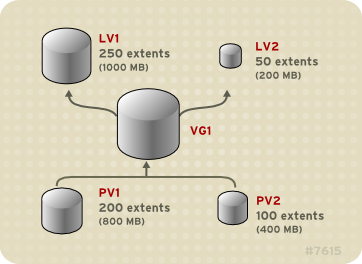

Figure 3.2. Extent Mapping

VG1 with a physical extent size of 4MB. This volume group includes 2 physical volumes named PV1 and PV2. The physical volumes are divided into 4MB units, since that is the extent size. In this example, PV1 is 200 extents in size (800MB) and PV2 is 100 extents in size (400MB). You can create a linear volume any size between 1 and 300 extents (4MB to 1200MB). In this example, the linear volume named LV1 is 300 extents in size.

Figure 3.3. Linear Volume with Unequal Physical Volumes

LV1, which is 250 extents in size (1000MB) and LV2 which is 50 extents in size (200MB).

Figure 3.4. Multiple Logical Volumes

3.3.2. Striped Logical Volumes

- the first stripe of data is written to PV1

- the second stripe of data is written to PV2

- the third stripe of data is written to PV3

- the fourth stripe of data is written to PV1

Figure 3.5. Striping Data Across Three PVs

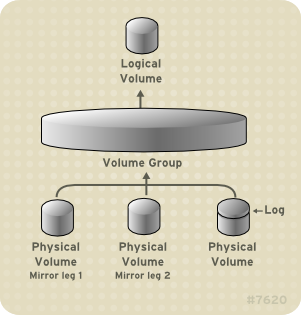

3.3.3. Mirrored Logical Volumes

Figure 3.6. Mirrored Logical Volume

3.3.4. RAID Logical Volumes

3.3.5. Thinly-Provisioned Logical Volumes (Thin Volumes)

Note

3.3.6. Snapshot Volumes

Note

Note

Note

/usr, would need less space than a long-lived snapshot of a volume that sees a greater number of writes, such as /home.

- Most typically, a snapshot is taken when you need to perform a backup on a logical volume without halting the live system that is continuously updating the data.

- You can execute the

fsckcommand on a snapshot file system to check the file system integrity and determine whether the original file system requires file system repair. - Because the snapshot is read/write, you can test applications against production data by taking a snapshot and running tests against the snapshot, leaving the real data untouched.

- You can create LVM volumes for use with Red Hat virtualization. LVM snapshots can be used to create snapshots of virtual guest images. These snapshots can provide a convenient way to modify existing guests or create new guests with minimal additional storage. For information on creating LVM-based storage pools with Red Hat Virtualization, see the Virtualization Administration Guide.

--merge option of the lvconvert command to merge a snapshot into its origin volume. One use for this feature is to perform system rollback if you have lost data or files or otherwise need to restore your system to a previous state. After you merge the snapshot volume, the resulting logical volume will have the origin volume's name, minor number, and UUID and the merged snapshot is removed. For information on using this option, see Section 5.4.8, “Merging Snapshot Volumes”.

3.3.7. Thinly-Provisioned Snapshot Volumes

- A thin snapshot volume can reduce disk usage when there are multiple snapshots of the same origin volume.

- If there are multiple snapshots of the same origin, then a write to the origin will cause one COW operation to preserve the data. Increasing the number of snapshots of the origin should yield no major slowdown.

- Thin snapshot volumes can be used as a logical volume origin for another snapshot. This allows for an arbitrary depth of recursive snapshots (snapshots of snapshots of snapshots...).

- A snapshot of a thin logical volume also creates a thin logical volume. This consumes no data space until a COW operation is required, or until the snapshot itself is written.

- A thin snapshot volume does not need to be activated with its origin, so a user may have only the origin active while there are many inactive snapshot volumes of the origin.

- When you delete the origin of a thinly-provisioned snapshot volume, each snapshot of that origin volume becomes an independent thinly-provisioned volume. This means that instead of merging a snapshot with its origin volume, you may choose to delete the origin volume and then create a new thinly-provisioned snapshot using that independent volume as the origin volume for the new snapshot.

- You cannot change the chunk size of a thin pool. If the thin pool has a large chunk size (for example, 1MB) and you require a short-living snapshot for which a chunk size that large is not efficient, you may elect to use the older snapshot feature.

- You cannot limit the size of a thin snapshot volume; the snapshot will use all of the space in the thin pool, if necessary. This may not be appropriate for your needs.

3.3.8. Cache Volumes

Chapter 4. LVM Administration Overview

4.1. Creating LVM Volumes in a Cluster

clvmd daemon, must be started at boot time, as described in Section 2.4, “The Clustered Logical Volume Manager (CLVM)”.

lvm.conf file for cluster-wide locking. Information on configuring the lvm.conf file to support clustered locking is provided within the lvm.conf file itself. For information about the lvm.conf file, see Appendix B, The LVM Configuration Files.

Warning

4.2. Logical Volume Creation Overview

- Initialize the partitions you will use for the LVM volume as physical volumes (this labels them).

- Create a volume group.

- Create a logical volume.

Note

- Create a GFS2 file system on the logical volume with the

mkfs.gfs2command. - Create a new mount point with the

mkdircommand. In a clustered system, create the mount point on all nodes in the cluster. - Mount the file system. You may want to add a line to the

fstabfile for each node in the system.

4.3. Growing a File System on a Logical Volume

- Make a new physical volume.

- Extend the volume group that contains the logical volume with the file system you are growing to include the new physical volume.

- Extend the logical volume to include the new physical volume.

- Grow the file system.

4.4. Logical Volume Backup

lvm.conf file. By default, the metadata backup is stored in the /etc/lvm/backup file and the metadata archives are stored in the /etc/lvm/archive file. How long the metadata archives stored in the /etc/lvm/archive file are kept and how many archive files are kept is determined by parameters you can set in the lvm.conf file. A daily system backup should include the contents of the /etc/lvm directory in the backup.

/etc/lvm/backup file with the vgcfgbackup command. You can restore metadata with the vgcfgrestore command. The vgcfgbackup and vgcfgrestore commands are described in Section 5.3.13, “Backing Up Volume Group Metadata”.

4.5. Logging

- standard output/error

- syslog

- log file

- external log function

/etc/lvm/lvm.conf file, which is described in Appendix B, The LVM Configuration Files.

4.6. The Metadata Daemon (lvmetad)

lvmetad) and a udev rule. The metadata daemon has two main purposes: It improves performance of LVM commands and it allows udev to automatically activate logical volumes or entire volume groups as they become available to the system.

Note

lvmetad daemon is not currently supported across the nodes of a cluster, and requires that the locking type be local file-based locking.

- Start the daemon through the

lvm2-lvmetadservice. To start the daemon automatically at boot time, use thechkconfig lvm2-lvmetad oncommand. To start the daemon manually, use theservice lvm2-lvmetad startcommand. - Configure LVM to make use of the daemon by setting the

global/use_lvmetadvariable to 1 in thelvm.confconfiguration file. For information on thelvm.confconfiguration file, see Appendix B, The LVM Configuration Files.

lvmetad daemon scans each device only once, when it becomes available, by means of udev rules. This can save a significant amount of I/O and reduce the time required to complete LVM operations, particularly on systems with many disks. For information on the udev device manager and udev rules, see Section A.3, “Device Mapper Support for the udev Device Manager”.

lvmetad daemon is enabled, the activation/auto_activation_volume_list option in the lvm.conf configuration file can be used to configure a list of volume groups and logical volumes that should be automatically activated. Without the lvmetad daemon, a manual activation is necessary. By default, this list is not defined, which means that all volumes are autoactivated once all of the physical volumes are in place. The autoactivation works recursively for LVM stacked on top of other devices, as it is event-based.

Note

lvmetad daemon is running, the filter = setting in the /etc/lvm/lvm.conf file does not apply when you execute the pvscan --cache device command. To filter devices, you need to use the global_filter = setting. Devices that fail the global filter are not opened by LVM and are never scanned. You may need to use a global filter, for example, when you use LVM devices in VMs and you do not want the contents of the devices in the VMs to be scanned by the physical host.

4.7. Displaying LVM Information with the lvm Command

lvm command provides several built-in options that you can use to display information about LVM support and configuration.

lvm devtypesDisplays the recognized built-in block device types (Red Hat Enterprise Linux release 6.6 and later).lvm formatsDisplays recognizes metadata formats.lvm helpDisplays LVM help text.lvm segtypesDisplays recognized logical volume segment types.lvm tagsDisplays any tags defined on this host. For information on LVM object tags, see Appendix D, LVM Object Tags.lvm versionDisplays the current version information.

Chapter 5. LVM Administration with CLI Commands

Note

clvmd daemon. For information, see Section 4.1, “Creating LVM Volumes in a Cluster”.

5.1. Using CLI Commands

--units argument in a command, lower-case indicates that units are in multiples of 1024 while upper-case indicates that units are in multiples of 1000.

lvol0 in a volume group called vg0 can be specified as vg0/lvol0. Where a list of volume groups is required but is left empty, a list of all volume groups will be substituted. Where a list of logical volumes is required but a volume group is given, a list of all the logical volumes in that volume group will be substituted. For example, the lvdisplay vg0 command will display all the logical volumes in volume group vg0.

-v argument, which can be entered multiple times to increase the output verbosity. For example, the following examples shows the default output of the lvcreate command.

lvcreate -L 50MB new_vg Rounding up size to full physical extent 52.00 MB Logical volume "lvol0" created

# lvcreate -L 50MB new_vg

Rounding up size to full physical extent 52.00 MB

Logical volume "lvol0" created

lvcreate command with the -v argument.

-vv, -vvv or the -vvvv argument to display increasingly more details about the command execution. The -vvvv argument provides the maximum amount of information at this time. The following example shows only the first few lines of output for the lvcreate command with the -vvvv argument specified.

--help argument of the command.

commandname --help

# commandname --helpman command:

man commandname

# man commandnameman lvm command provides general online information about LVM.

/dev/sdf which is part of a volume group and, when you plug it back in, you find that it is now /dev/sdk. LVM will still find the physical volume because it identifies the physical volume by its UUID and not its device name. For information on specifying the UUID of a physical volume when creating a physical volume, see Section 7.4, “Recovering Physical Volume Metadata”.

5.2. Physical Volume Administration

5.2.1. Creating Physical Volumes

5.2.1.1. Setting the Partition Type

fdisk or cfdisk command or an equivalent. For whole disk devices only the partition table must be erased, which will effectively destroy all data on that disk. You can remove an existing partition table by zeroing the first sector with the following command:

dd if=/dev/zero of=PhysicalVolume bs=512 count=1

# dd if=/dev/zero of=PhysicalVolume bs=512 count=15.2.1.2. Initializing Physical Volumes

pvcreate command to initialize a block device to be used as a physical volume. Initialization is analogous to formatting a file system.

/dev/sdd, /dev/sde, and /dev/sdf as LVM physical volumes for later use as part of LVM logical volumes.

pvcreate /dev/sdd /dev/sde /dev/sdf

# pvcreate /dev/sdd /dev/sde /dev/sdfpvcreate command on the partition. The following example initializes the partition /dev/hdb1 as an LVM physical volume for later use as part of an LVM logical volume.

pvcreate /dev/hdb1

# pvcreate /dev/hdb15.2.1.3. Scanning for Block Devices

lvmdiskscan command, as shown in the following example.

5.2.2. Displaying Physical Volumes

pvs, pvdisplay, and pvscan.

pvs command provides physical volume information in a configurable form, displaying one line per physical volume. The pvs command provides a great deal of format control, and is useful for scripting. For information on using the pvs command to customize your output, see Section 5.8, “Customized Reporting for LVM”.

pvdisplay command provides a verbose multi-line output for each physical volume. It displays physical properties (size, extents, volume group, and so on) in a fixed format.

pvdisplay command for a single physical volume.

pvscan command scans all supported LVM block devices in the system for physical volumes.

/etc/lvm/lvm.conf file so that this command will avoid scanning specific physical volumes. For information on using filters to control which devices are scanned, see Section 5.5, “Controlling LVM Device Scans with Filters”.

5.2.3. Preventing Allocation on a Physical Volume

pvchange command. This may be necessary if there are disk errors, or if you will be removing the physical volume.

/dev/sdk1.

pvchange -x n /dev/sdk1

# pvchange -x n /dev/sdk1-xy arguments of the pvchange command to allow allocation where it had previously been disallowed.

5.2.4. Resizing a Physical Volume

pvresize command to update LVM with the new size. You can execute this command while LVM is using the physical volume.

5.2.5. Removing Physical Volumes

pvremove command. Executing the pvremove command zeroes the LVM metadata on an empty physical volume.

vgreduce command, as described in Section 5.3.7, “Removing Physical Volumes from a Volume Group”.

pvremove /dev/ram15 Labels on physical volume "/dev/ram15" successfully wiped

# pvremove /dev/ram15

Labels on physical volume "/dev/ram15" successfully wiped

5.3. Volume Group Administration

5.3.1. Creating Volume Groups

vgcreate command. The vgcreate command creates a new volume group by name and adds at least one physical volume to it.

vg1 that contains physical volumes /dev/sdd1 and /dev/sde1.

vgcreate vg1 /dev/sdd1 /dev/sde1

# vgcreate vg1 /dev/sdd1 /dev/sde1-s option to the vgcreate command if the default extent size is not suitable. You can put limits on the number of physical or logical volumes the volume group can have by using the -p and -l arguments of the vgcreate command.

normal allocation policy. You can use the --alloc argument of the vgcreate command to specify an allocation policy of contiguous, anywhere, or cling. In general, allocation policies other than normal are required only in special cases where you need to specify unusual or nonstandard extent allocation. For further information on how LVM allocates physical extents, see Section 5.3.2, “LVM Allocation”.

/dev directory with the following layout:

/dev/vg/lv/

/dev/vg/lv/

myvg1 and myvg2, each with three logical volumes named lv01, lv02, and lv03, six device special files are created:

5.3.2. LVM Allocation

- The complete set of unallocated physical extents in the volume group is generated for consideration. If you supply any ranges of physical extents at the end of the command line, only unallocated physical extents within those ranges on the specified physical volumes are considered.

- Each allocation policy is tried in turn, starting with the strictest policy (

contiguous) and ending with the allocation policy specified using the--allocoption or set as the default for the particular logical volume or volume group. For each policy, working from the lowest-numbered logical extent of the empty logical volume space that needs to be filled, as much space as possible is allocated, according to the restrictions imposed by the allocation policy. If more space is needed, LVM moves on to the next policy.

- An allocation policy of

contiguousrequires that the physical location of any logical extent that is not the first logical extent of a logical volume is adjacent to the physical location of the logical extent immediately preceding it.When a logical volume is striped or mirrored, thecontiguousallocation restriction is applied independently to each stripe or mirror image (leg) that needs space. - An allocation policy of

clingrequires that the physical volume used for any logical extent to be added to an existing logical volume is already in use by at least one logical extent earlier in that logical volume. If the configuration parameterallocation/cling_tag_listis defined, then two physical volumes are considered to match if any of the listed tags is present on both physical volumes. This allows groups of physical volumes with similar properties (such as their physical location) to be tagged and treated as equivalent for allocation purposes. For more information on using theclingpolicy in conjunction with LVM tags to specify which additional physical volumes to use when extending an LVM volume, see Section 5.4.14.3, “Extending a Logical Volume with theclingAllocation Policy”.When a Logical Volume is striped or mirrored, theclingallocation restriction is applied independently to each stripe or mirror image (leg) that needs space. - An allocation policy of

normalwill not choose a physical extent that shares the same physical volume as a logical extent already allocated to a parallel logical volume (that is, a different stripe or mirror image/leg) at the same offset within that parallel logical volume.When allocating a mirror log at the same time as logical volumes to hold the mirror data, an allocation policy ofnormalwill first try to select different physical volumes for the log and the data. If that is not possible and theallocation/mirror_logs_require_separate_pvsconfiguration parameter is set to 0, it will then allow the log to share physical volume(s) with part of the data.Similarly, when allocating thin pool metadata, an allocation policy ofnormalwill follow the same considerations as for allocation of a mirror log, based on the value of theallocation/thin_pool_metadata_require_separate_pvsconfiguration parameter. - If there are sufficient free extents to satisfy an allocation request but a

normalallocation policy would not use them, theanywhereallocation policy will, even if that reduces performance by placing two stripes on the same physical volume.

vgchange command.

Note

lvcreate and lvconvert steps such that the allocation policies applied to each step leave LVM no discretion over the layout.

-vvvv option to a command.

5.3.3. Creating Volume Groups in a Cluster

vgcreate command, just as you create them on a single node.

-c n option of the vgcreate command.

vg1 that contains physical volumes /dev/sdd1 and /dev/sde1.

vgcreate -c n vg1 /dev/sdd1 /dev/sde1

# vgcreate -c n vg1 /dev/sdd1 /dev/sde1-c option of the vgchange command, which is described in Section 5.3.8, “Changing the Parameters of a Volume Group”.

vgs command, which displays the c attribute if the volume is clustered. The following command displays the attributes of the volume groups VolGroup00 and testvg1. In this example, VolGroup00 is not clustered, while testvg1 is clustered, as indicated by the c attribute under the Attr heading.

vgs VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree VolGroup00 1 2 0 wz--n- 19.88G 0 testvg1 1 1 0 wz--nc 46.00G 8.00M

# vgs

VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree

VolGroup00 1 2 0 wz--n- 19.88G 0

testvg1 1 1 0 wz--nc 46.00G 8.00M

vgs command, see Section 5.3.5, “Displaying Volume Groups”Section 5.8, “Customized Reporting for LVM”, and the vgs man page.

5.3.4. Adding Physical Volumes to a Volume Group

vgextend command. The vgextend command increases a volume group's capacity by adding one or more free physical volumes.

/dev/sdf1 to the volume group vg1.

vgextend vg1 /dev/sdf1

# vgextend vg1 /dev/sdf15.3.5. Displaying Volume Groups

vgs and vgdisplay.

vgscan command, which scans all the disks for volume groups and rebuilds the LVM cache file, also displays the volume groups. For information on the vgscan command, see Section 5.3.6, “Scanning Disks for Volume Groups to Build the Cache File”.

vgs command provides volume group information in a configurable form, displaying one line per volume group. The vgs command provides a great deal of format control, and is useful for scripting. For information on using the vgs command to customize your output, see Section 5.8, “Customized Reporting for LVM”.

vgdisplay command displays volume group properties (such as size, extents, number of physical volumes, and so on) in a fixed form. The following example shows the output of a vgdisplay command for the volume group new_vg. If you do not specify a volume group, all existing volume groups are displayed.

5.3.6. Scanning Disks for Volume Groups to Build the Cache File

vgscan command scans all supported disk devices in the system looking for LVM physical volumes and volume groups. This builds the LVM cache file in the /etc/lvm/cache/.cache file, which maintains a listing of current LVM devices.

vgscan command automatically at system startup and at other times during LVM operation, such as when you execute a vgcreate command or when LVM detects an inconsistency.

Note

vgscan command manually when you change your hardware configuration and add or delete a device from a node, causing new devices to be visible to the system that were not present at system bootup. This may be necessary, for example, when you add new disks to the system on a SAN or hotplug a new disk that has been labeled as a physical volume.

lvm.conf file to restrict the scan to avoid specific devices. For information on using filters to control which devices are scanned, see Section 5.5, “Controlling LVM Device Scans with Filters”.

vgscan command.

vgscan Reading all physical volumes. This may take a while... Found volume group "new_vg" using metadata type lvm2 Found volume group "officevg" using metadata type lvm2

# vgscan

Reading all physical volumes. This may take a while...

Found volume group "new_vg" using metadata type lvm2

Found volume group "officevg" using metadata type lvm2

5.3.7. Removing Physical Volumes from a Volume Group

vgreduce command. The vgreduce command shrinks a volume group's capacity by removing one or more empty physical volumes. This frees those physical volumes to be used in different volume groups or to be removed from the system.

pvdisplay command.

pvmove command. Then use the vgreduce command to remove the physical volume.

/dev/hda1 from the volume group my_volume_group.

vgreduce my_volume_group /dev/hda1

# vgreduce my_volume_group /dev/hda1--removemissing parameter of the vgreduce command, if there are no logical volumes that are allocated on the missing physical volumes.

5.3.8. Changing the Parameters of a Volume Group

vgchange command is used to deactivate and activate volume groups, as described in Section 5.3.9, “Activating and Deactivating Volume Groups”. You can also use this command to change several volume group parameters for an existing volume group.

vg00 to 128.

vgchange -l 128 /dev/vg00

# vgchange -l 128 /dev/vg00vgchange command, see the vgchange(8) man page.

5.3.9. Activating and Deactivating Volume Groups

-a (--available) argument of the vgchange command.

my_volume_group.

vgchange -a n my_volume_group

# vgchange -a n my_volume_grouplvchange command, as described in Section 5.4.10, “Changing the Parameters of a Logical Volume Group”, For information on activating logical volumes on individual nodes in a cluster, see Section 5.7, “Activating Logical Volumes on Individual Nodes in a Cluster”.

5.3.10. Removing Volume Groups

vgremove command.

vgremove officevg Volume group "officevg" successfully removed

# vgremove officevg

Volume group "officevg" successfully removed

5.3.11. Splitting a Volume Group

vgsplit command.

pvmove command to force the split.

smallvg from the original volume group bigvg.

vgsplit bigvg smallvg /dev/ram15 Volume group "smallvg" successfully split from "bigvg"

# vgsplit bigvg smallvg /dev/ram15

Volume group "smallvg" successfully split from "bigvg"

5.3.12. Combining Volume Groups

vgmerge command. You can merge an inactive "source" volume with an active or an inactive "destination" volume if the physical extent sizes of the volume are equal and the physical and logical volume summaries of both volume groups fit into the destination volume groups limits.

my_vg into the active or inactive volume group databases giving verbose runtime information.

vgmerge -v databases my_vg

# vgmerge -v databases my_vg5.3.13. Backing Up Volume Group Metadata

lvm.conf file. By default, the metadata backup is stored in the /etc/lvm/backup file and the metadata archives are stored in the /etc/lvm/archives file. You can manually back up the metadata to the /etc/lvm/backup file with the vgcfgbackup command.

vgcfrestore command restores the metadata of a volume group from the archive to all the physical volumes in the volume groups.

vgcfgrestore command to recover physical volume metadata, see Section 7.4, “Recovering Physical Volume Metadata”.

5.3.14. Renaming a Volume Group

vgrename command to rename an existing volume group.

vg02 to my_volume_group

vgrename /dev/vg02 /dev/my_volume_group

# vgrename /dev/vg02 /dev/my_volume_groupvgrename vg02 my_volume_group

# vgrename vg02 my_volume_group5.3.15. Moving a Volume Group to Another System

vgexport and vgimport commands when you do this.

Note

--force argument of the vgimport command. This allows you to import volume groups that are missing physical volumes and subsequently run the vgreduce --removemissing command.

vgexport command makes an inactive volume group inaccessible to the system, which allows you to detach its physical volumes. The vgimport command makes a volume group accessible to a machine again after the vgexport command has made it inactive.

- Make sure that no users are accessing files on the active volumes in the volume group, then unmount the logical volumes.

- Use the

-a nargument of thevgchangecommand to mark the volume group as inactive, which prevents any further activity on the volume group. - Use the

vgexportcommand to export the volume group. This prevents it from being accessed by the system from which you are removing it.After you export the volume group, the physical volume will show up as being in an exported volume group when you execute thepvscancommand, as in the following example.Copy to Clipboard Copied! Toggle word wrap Toggle overflow When the system is next shut down, you can unplug the disks that constitute the volume group and connect them to the new system. - When the disks are plugged into the new system, use the

vgimportcommand to import the volume group, making it accessible to the new system. - Activate the volume group with the

-a yargument of thevgchangecommand. - Mount the file system to make it available for use.

5.3.16. Recreating a Volume Group Directory

vgmknodes command. This command checks the LVM2 special files in the /dev directory that are needed for active logical volumes. It creates any special files that are missing removes unused ones.

vgmknodes command into the vgscan command by specifying the mknodes argument to the vgscan command.

5.4. Logical Volume Administration

5.4.1. Creating Linear Logical Volumes

lvcreate command. If you do not specify a name for the logical volume, the default name lvol# is used where # is the internal number of the logical volume.

vg1.

lvcreate -L 10G vg1

# lvcreate -L 10G vg1testlv in the volume group testvg, creating the block device /dev/testvg/testlv.

lvcreate -L 1500 -n testlv testvg

# lvcreate -L 1500 -n testlv testvggfslv from the free extents in volume group vg0.

lvcreate -L 50G -n gfslv vg0

# lvcreate -L 50G -n gfslv vg0-l argument of the lvcreate command to specify the size of the logical volume in extents. You can also use this argument to specify the percentage of the volume group to use for the logical volume. The following command creates a logical volume called mylv that uses 60% of the total space in volume group testvg.

lvcreate -l 60%VG -n mylv testvg

# lvcreate -l 60%VG -n mylv testvg-l argument of the lvcreate command to specify the percentage of the remaining free space in a volume group as the size of the logical volume. The following command creates a logical volume called yourlv that uses all of the unallocated space in the volume group testvg.

lvcreate -l 100%FREE -n yourlv testvg

# lvcreate -l 100%FREE -n yourlv testvg-l argument of the lvcreate command to create a logical volume that uses the entire volume group. Another way to create a logical volume that uses the entire volume group is to use the vgdisplay command to find the "Total PE" size and to use those results as input to the lvcreate command.

mylv that fills the volume group named testvg.

vgdisplay testvg | grep "Total PE" Total PE 10230 lvcreate -l 10230 testvg -n mylv

# vgdisplay testvg | grep "Total PE"

Total PE 10230

# lvcreate -l 10230 testvg -n mylvlvcreate command line. The following command creates a logical volume named testlv in volume group testvg allocated from the physical volume /dev/sdg1,

lvcreate -L 1500 -ntestlv testvg /dev/sdg1

# lvcreate -L 1500 -ntestlv testvg /dev/sdg1/dev/sda1 and extents 50 through 124 of physical volume /dev/sdb1 in volume group testvg.

lvcreate -l 100 -n testlv testvg /dev/sda1:0-24 /dev/sdb1:50-124

# lvcreate -l 100 -n testlv testvg /dev/sda1:0-24 /dev/sdb1:50-124/dev/sda1 and then continues laying out the logical volume at extent 100.

lvcreate -l 100 -n testlv testvg /dev/sda1:0-25:100-

# lvcreate -l 100 -n testlv testvg /dev/sda1:0-25:100-inherit, which applies the same policy as for the volume group. These policies can be changed using the lvchange command. For information on allocation policies, see Section 5.3.1, “Creating Volume Groups”.

5.4.2. Creating Striped Volumes

-i argument of the lvcreate command. This determines over how many physical volumes the logical volume will be striped. The number of stripes cannot be greater than the number of physical volumes in the volume group (unless the --alloc anywhere argument is used).

gfslv, and is carved out of volume group vg0.

lvcreate -L 50G -i2 -I64 -n gfslv vg0

# lvcreate -L 50G -i2 -I64 -n gfslv vg0stripelv and is in volume group testvg. The stripe will use sectors 0-49 of /dev/sda1 and sectors 50-99 of /dev/sdb1.

lvcreate -l 100 -i2 -nstripelv testvg /dev/sda1:0-49 /dev/sdb1:50-99 Using default stripesize 64.00 KB Logical volume "stripelv" created

# lvcreate -l 100 -i2 -nstripelv testvg /dev/sda1:0-49 /dev/sdb1:50-99

Using default stripesize 64.00 KB

Logical volume "stripelv" created

5.4.3. Creating Mirrored Volumes

Note

Note

lvm.conf file must be set correctly to enable cluster locking. For an example of creating a mirrored volume in a cluster, see Section 6.5, “Creating a Mirrored LVM Logical Volume in a Cluster”.

-m argument of the lvcreate command. Specifying -m1 creates one mirror, which yields two copies of the file system: a linear logical volume plus one copy. Similarly, specifying -m2 creates two mirrors, yielding three copies of the file system.

mirrorlv, and is carved out of volume group vg0:

lvcreate -L 50G -m1 -n mirrorlv vg0

# lvcreate -L 50G -m1 -n mirrorlv vg0-R argument of the lvcreate command to specify the region size in megabytes. You can also change the default region size by editing the mirror_region_size setting in the lvm.conf file.

Note

-R argument to the lvcreate command. For example, if your mirror size is 1.5TB, you could specify -R 2. If your mirror size is 3TB, you could specify -R 4. For a mirror size of 5TB, you could specify -R 8.

lvcreate -m1 -L 2T -R 2 -n mirror vol_group

# lvcreate -m1 -L 2T -R 2 -n mirror vol_group--nosync argument to indicate that an initial synchronization from the first device is not required.

--mirrorlog core argument; this eliminates the need for an extra log device, but it requires that the entire mirror be resynchronized at every reboot.

bigvg. The logical volume is named ondiskmirvol and has a single mirror. The volume is 12MB in size and keeps the mirror log in memory.

lvcreate -L 12MB -m1 --mirrorlog core -n ondiskmirvol bigvg Logical volume "ondiskmirvol" created

# lvcreate -L 12MB -m1 --mirrorlog core -n ondiskmirvol bigvg

Logical volume "ondiskmirvol" created

--alloc anywhere argument of the vgcreate command. This may degrade performance, but it allows you to create a mirror even if you have only two underlying devices.

vg0 consists of only two devices. This command creates a 500 MB volume named mirrorlv in the vg0 volume group.

lvcreate -L 500M -m1 -n mirrorlv -alloc anywhere vg0

# lvcreate -L 500M -m1 -n mirrorlv -alloc anywhere vg0Note

--mirrorlog mirrored argument. The following command creates a mirrored logical volume from the volume group bigvg. The logical volume is named twologvol and has a single mirror. The volume is 12MB in size and the mirror log is mirrored, with each log kept on a separate device.

lvcreate -L 12MB -m1 --mirrorlog mirrored -n twologvol bigvg Logical volume "twologvol" created

# lvcreate -L 12MB -m1 --mirrorlog mirrored -n twologvol bigvg

Logical volume "twologvol" created

--alloc anywhere argument of the vgcreate command. This may degrade performance, but it allows you to create a redundant mirror log even if you do not have sufficient underlying devices for each log to be kept on a separate device than the mirror legs.

--nosync argument to indicate that an initial synchronization from the first device is not required.

mirrorlv, and it is carved out of volume group vg0. The first leg of the mirror is on device /dev/sda1, the second leg of the mirror is on device /dev/sdb1, and the mirror log is on /dev/sdc1.

lvcreate -L 500M -m1 -n mirrorlv vg0 /dev/sda1 /dev/sdb1 /dev/sdc1

# lvcreate -L 500M -m1 -n mirrorlv vg0 /dev/sda1 /dev/sdb1 /dev/sdc1mirrorlv, and it is carved out of volume group vg0. The first leg of the mirror is on extents 0 through 499 of device /dev/sda1, the second leg of the mirror is on extents 0 through 499 of device /dev/sdb1, and the mirror log starts on extent 0 of device /dev/sdc1. These are 1MB extents. If any of the specified extents have already been allocated, they will be ignored.

lvcreate -L 500M -m1 -n mirrorlv vg0 /dev/sda1:0-499 /dev/sdb1:0-499 /dev/sdc1:0

# lvcreate -L 500M -m1 -n mirrorlv vg0 /dev/sda1:0-499 /dev/sdb1:0-499 /dev/sdc1:0Note

--mirrors X) and the number of stripes (--stripes Y) results in a mirror device whose constituent devices are striped.

5.4.3.1. Mirrored Logical Volume Failure Policy

mirror_image_fault_policy and mirror_log_fault_policy parameters in the activation section of the lvm.conf file. When these parameters are set to remove, the system attempts to remove the faulty device and run without it. When this parameter is set to allocate, the system attempts to remove the faulty device and tries to allocate space on a new device to be a replacement for the failed device; this policy acts like the remove policy if no suitable device and space can be allocated for the replacement.

mirror_log_fault_policy parameter is set to allocate. Using this policy for the log is fast and maintains the ability to remember the sync state through crashes and reboots. If you set this policy to remove, when a log device fails the mirror converts to using an in-memory log and the mirror will not remember its sync status across crashes and reboots and the entire mirror will be resynced.

mirror_image_fault_policy parameter is set to remove. With this policy, if a mirror image fails the mirror will convert to a non-mirrored device if there is only one remaining good copy. Setting this policy to allocate for a mirror device requires the mirror to resynchronize the devices; this is a slow process, but it preserves the mirror characteristic of the device.

Note

mirror_log_fault_policy parameter is set to allocate, is to attempt to replace any of the failed devices. Note, however, that there is no guarantee that the second stage will choose devices previously in-use by the mirror that had not been part of the failure if others are available.

5.4.3.2. Splitting Off a Redundant Image of a Mirrored Logical Volume

--splitmirrors argument of the lvconvert command, specifying the number of redundant images to split off. You must use the --name argument of the command to specify a name for the newly-split-off logical volume.

copy from the mirrored logical volume vg/lv. The new logical volume contains two mirror legs. In this example, LVM selects which devices to split off.

lvconvert --splitmirrors 2 --name copy vg/lv

# lvconvert --splitmirrors 2 --name copy vg/lvcopy from the mirrored logical volume vg/lv. The new logical volume contains two mirror legs consisting of devices /dev/sdc1 and /dev/sde1.

lvconvert --splitmirrors 2 --name copy vg/lv /dev/sd[ce]1

# lvconvert --splitmirrors 2 --name copy vg/lv /dev/sd[ce]15.4.3.3. Repairing a Mirrored Logical Device

lvconvert --repair command to repair a mirror after a disk failure. This brings the mirror back into a consistent state. The lvconvert --repair command is an interactive command that prompts you to indicate whether you want the system to attempt to replace any failed devices.

- To skip the prompts and replace all of the failed devices, specify the

-yoption on the command line. - To skip the prompts and replace none of the failed devices, specify the

-foption on the command line. - To skip the prompts and still indicate different replacement policies for the mirror image and the mirror log, you can specify the

--use-policiesargument to use the device replacement policies specified by themirror_log_fault_policyandmirror_device_fault_policyparameters in thelvm.conffile.

5.4.3.4. Changing Mirrored Volume Configuration

lvconvert command. This allows you to convert a logical volume from a mirrored volume to a linear volume or from a linear volume to a mirrored volume. You can also use this command to reconfigure other mirror parameters of an existing logical volume, such as corelog.

lvconvert command to restore the mirror. This procedure is provided in Section 7.3, “Recovering from LVM Mirror Failure”.

vg00/lvol1 to a mirrored logical volume.

lvconvert -m1 vg00/lvol1

# lvconvert -m1 vg00/lvol1vg00/lvol1 to a linear logical volume, removing the mirror leg.

lvconvert -m0 vg00/lvol1

# lvconvert -m0 vg00/lvol1vg00/lvol1. This example shows the configuration of the volume before and after the lvconvert command changed the volume to a volume with two mirror legs.

5.4.4. Creating Thinly-Provisioned Logical Volumes

Note

lvmthin(7) man page.

Note

- Create a volume group with the

vgcreatecommand. - Create a thin pool with the

lvcreatecommand. - Create a thin volume in the thin pool with the

lvcreatecommand.

-T (or --thin) option of the lvcreate command to create either a thin pool or a thin volume. You can also use -T option of the lvcreate command to create both a thin pool and a thin volume in that pool at the same time with a single command.

-T option of the lvcreate command to create a thin pool named mythinpool that is in the volume group vg001 and that is 100M in size. Note that since you are creating a pool of physical space, you must specify the size of the pool. The -T option of the lvcreate command does not take an argument; it deduces what type of device is to be created from the other options the command specifies.

-T option of the lvcreate command to create a thin volume named thinvolume in the thin pool vg001/mythinpool. Note that in this case you are specifying virtual size, and that you are specifying a virtual size for the volume that is greater than the pool that contains it.

-T option of the lvcreate command to create a thin pool and a thin volume in that pool by specifying both a size and a virtual size argument for the lvcreate command. This command creates a thin pool named mythinpool in the volume group vg001 and it also creates a thin volume named thinvolume in that pool.

--thinpool parameter of the lvcreate command. Unlike the -T option, the --thinpool parameter requires an argument, which is the name of the thin pool logical volume that you are creating. The following example specifies the --thinpool parameter of the lvcreate command to create a thin pool named mythinpool that is in the volume group vg001 and that is 100M in size:

pool in volume group vg001 with two 64 kB stripes and a chunk size of 256 kB. It also creates a 1T thin volume, vg00/thin_lv.

lvcreate -i 2 -I 64 -c 256 -L100M -T vg00/pool -V 1T --name thin_lv

# lvcreate -i 2 -I 64 -c 256 -L100M -T vg00/pool -V 1T --name thin_lvlvextend command. You cannot, however, reduce the size of a thin pool.

lvrename, you can remove the volume with the lvremove, and you can display information about the volume with the lvs and lvdisplay commands.

lvcreate command sets the size of the thin pool's metadata logical volume according to the formula (Pool_LV_size / Pool_LV_chunk_size * 64). You cannot currently resize the metadata volume, however, so if you expect significant growth of the size of thin pool at a later time you should increase this value with the --poolmetadatasize parameter of the lvcreate command. The supported value for the thin pool's metadata logical volume is in the range between 2MiB and 16GiB.

--thinpool parameter of the lvconvert command to convert an existing logical volume to a thin pool volume. When you convert an existing logical volume to a thin pool volume, you must use the --poolmetadata parameter in conjunction with the --thinpool parameter of the lvconvert to convert an existing logical volume to the thin pool volume's metadata volume.

Note

lvconvert does not preserve the content of the devices but instead overwrites the content.

lv1 in volume group vg001 to a thin pool volume and converts the existing logical volume lv2 in volume group vg001 to the metadata volume for that thin pool volume.

lvconvert --thinpool vg001/lv1 --poolmetadata vg001/lv2 Converted vg001/lv1 to thin pool.

# lvconvert --thinpool vg001/lv1 --poolmetadata vg001/lv2

Converted vg001/lv1 to thin pool.

5.4.5. Creating Snapshot Volumes

Note

-s argument of the lvcreate command to create a snapshot volume. A snapshot volume is writable.

Note

Note

/dev/vg00/snap. This creates a snapshot of the origin logical volume named /dev/vg00/lvol1. If the original logical volume contains a file system, you can mount the snapshot logical volume on an arbitrary directory in order to access the contents of the file system to run a backup while the original file system continues to get updated.

lvcreate --size 100M --snapshot --name snap /dev/vg00/lvol1

# lvcreate --size 100M --snapshot --name snap /dev/vg00/lvol1lvdisplay command yields output that includes a list of all snapshot logical volumes and their status (active or inactive).

/dev/new_vg/lvol0, for which a snapshot volume /dev/new_vg/newvgsnap has been created.

lvs command, by default, displays the origin volume and the current percentage of the snapshot volume being used for each snapshot volume. The following example shows the default output for the lvs command for a system that includes the logical volume /dev/new_vg/lvol0, for which a snapshot volume /dev/new_vg/newvgsnap has been created.

lvs LV VG Attr LSize Origin Snap% Move Log Copy% lvol0 new_vg owi-a- 52.00M newvgsnap1 new_vg swi-a- 8.00M lvol0 0.20

# lvs

LV VG Attr LSize Origin Snap% Move Log Copy%

lvol0 new_vg owi-a- 52.00M

newvgsnap1 new_vg swi-a- 8.00M lvol0 0.20

Warning

lvs command to be sure it does not fill. A snapshot that is 100% full is lost completely, as a write to unchanged parts of the origin would be unable to succeed without corrupting the snapshot.

snapshot_autoextend_threshold option in the lvm.conf file. This option allows automatic extension of a snapshot whenever the remaining snapshot space drops below the threshold you set. This feature requires that there be unallocated space in the volume group.

snapshot_autoextend_threshold and snapshot_autoextend_percent is provided in the lvm.conf file itself. For information about the lvm.conf file, see Appendix B, The LVM Configuration Files.

5.4.6. Creating Thinly-Provisioned Snapshot Volumes

Note

lvmthin(7) man page.

Important

lvcreate -s vg/thinvolume -L10M will not create a thin snapshot, even though the origin volume is a thin volume.

--name option of the lvcreate command. It is recommended that you use this option when creating a logical volume so that you can more easily see the volume you have created when you display logical volumes with the lvs command.

vg001/thinvolume that is named mysnapshot1.

--thinpool option. The following command creates a thin snapshot volume of the read-only inactive volume origin_volume. The thin snapshot volume is named mythinsnap. The logical volume origin_volume then becomes the thin external origin for the thin shapshot volume mythinsnap in volume group vg001 that will use the existing thin pool vg001/pool. Because the origin volume must be in the same volume group as the snapshot volume, you do not need to specify the volume group when specifying the origin logical volume.

lvcreate -s --thinpool vg001/pool origin_volume --name mythinsnap

# lvcreate -s --thinpool vg001/pool origin_volume --name mythinsnaplvcreate -s vg001/mythinsnap --name my2ndthinsnap

# lvcreate -s vg001/mythinsnap --name my2ndthinsnap5.4.7. Creating LVM Cache Logical Volumes

- Origin logical volume — the large, slow logical volume

- Cache pool logical volume — the small, fast logical volume, which is composed of two devices: the cache data logical volume, and the cache metadata logical volume

- Cache data logical volume — the logical volume containing the data blocks for the cache pool logical volume

- Cache metadata logical volume — the logical volume containing the metadata for the cache pool logical volume, which holds the accounting information that specifies where data blocks are stored (for example, on the origin logical volume or the cache data logical volume).

- Cache logical volume — the logical volume containing the origin logical volume and the cache pool logical volume. This is the resultant usable device which encapsulates the various cache volume components.

- Create a volume group that contains a slow physical volume and a fast physical volume. In this example.

/dev/sde1is a slow device and/dev/sdf1is a fast device and both devices are contained in volume groupVG.pvcreate /dev/sde1 pvcreate /dev/sdf1 vgcreate VG /dev/sde1 /dev/sdf1

# pvcreate /dev/sde1 # pvcreate /dev/sdf1 # vgcreate VG /dev/sde1 /dev/sdf1Copy to Clipboard Copied! Toggle word wrap Toggle overflow - Create the origin volume. This example creates an origin volume named

lvthat is 4G in size and that consists of/dev/sde1, the slow physical volume.lvcreate -L 4G -n lv VG /dev/sde1

# lvcreate -L 4G -n lv VG /dev/sde1Copy to Clipboard Copied! Toggle word wrap Toggle overflow - Create the cache data logical volume. This logical volume will hold data blocks from the origin volume. The size of this logical volume is the size of the cache and will be reported as the size of the cache pool logical volume. This example creates the cache data volume named

lv_cache. It is 2G in size and is contained on the fast device/dev/sdf1, which is part of the volume groupVG.lvcreate -L 2G -n lv_cache VG /dev/sdf1

# lvcreate -L 2G -n lv_cache VG /dev/sdf1Copy to Clipboard Copied! Toggle word wrap Toggle overflow - Create the cache metadata logical volume. This logical volume will hold cache pool metadata. The ratio of the size of the cache data logical volume to the size of the cache metadata logical volume should be about 1000:1, with a minimum size of 8MiB for the cache metadata logical volume. This example creates the cache metadata volume named

lv_cache_meta. It is 12M in size and is also contained on the fast device/dev/sdf1, which is part of the volume groupVG.lvcreate -L 12M -n lv_cache_meta VG /dev/sdf1

# lvcreate -L 12M -n lv_cache_meta VG /dev/sdf1Copy to Clipboard Copied! Toggle word wrap Toggle overflow - Create the cache pool logical volume by combining the cache data and the cache metadata logical volumes into a logical volume of type

cache-pool. You can set the behavior of the cache pool in this step; in this example thecachemodeargument is set towritethrough, which indicates that a write is considered complete only when it has been stored in both the cache pool logical volume and on the origin logical volume.When you execute this command, the cache data logical volume is renamed with_cdataappended to the original name of the cache data logical volume, and the cache metadata logical volume is renamed with_cmetaappended to the original name of the cache data logical volume; both of these volumes become hidden.Copy to Clipboard Copied! Toggle word wrap Toggle overflow - Create the cache logical volume by combining the cache pool logical volume with the origin logical volume. The user-accessible cache logical volume takes the name of the origin logical volume. The origin logical volume becomes a hidden logical volume with

_corigappended to the original name. You can execute this command when the origin logical volume is in use.Copy to Clipboard Copied! Toggle word wrap Toggle overflow

lvmcache(7) man page.

5.4.8. Merging Snapshot Volumes

--merge option of the lvconvert command to merge a snapshot into its origin volume. If both the origin and snapshot volume are not open, the merge will start immediately. Otherwise, the merge will start the first time either the origin or snapshot are activated and both are closed. Merging a snapshot into an origin that cannot be closed, for example a root file system, is deferred until the next time the origin volume is activated. When merging starts, the resulting logical volume will have the origin’s name, minor number and UUID. While the merge is in progress, reads or writes to the origin appear as they were directed to the snapshot being merged. When the merge finishes, the merged snapshot is removed.

vg00/lvol1_snap into its origin.

lvconvert --merge vg00/lvol1_snap

# lvconvert --merge vg00/lvol1_snapvg00/lvol1, vg00/lvol2, and vg00/lvol3 are all tagged with the tag @some_tag. The following command merges the snapshot logical volumes for all three volumes serially: vg00/lvol1, then vg00/lvol2, then vg00/lvol3. If the --background option were used, all snapshot logical volume merges would start in parallel.

lvconvert --merge @some_tag

# lvconvert --merge @some_taglvconvert --merge command, see the lvconvert(8) man page.

5.4.9. Persistent Device Numbers

lvcreate and the lvchange commands by using the following arguments:

--persistent y --major major --minor minor

--persistent y --major major --minor minorfsid parameter in the exports file may avoid the need to set a persistent device number within LVM.

5.4.10. Changing the Parameters of a Logical Volume Group

lvchange command. For a listing of the parameters you can change, see the lvchange(8) man page.

lvchange command to activate and deactivate logical volumes. To activate and deactivate all the logical volumes in a volume group at the same time, use the vgchange command, as described in Section 5.3.8, “Changing the Parameters of a Volume Group”.

lvol1 in volume group vg00 to be read-only.

lvchange -pr vg00/lvol1

# lvchange -pr vg00/lvol15.4.11. Renaming Logical Volumes

lvrename command.

lvold in volume group vg02 to lvnew.

lvrename /dev/vg02/lvold /dev/vg02/lvnew

# lvrename /dev/vg02/lvold /dev/vg02/lvnewlvrename vg02 lvold lvnew

# lvrename vg02 lvold lvnew5.4.12. Removing Logical Volumes

lvremove command. If the logical volume is currently mounted, unmount the volume before removing it. In addition, in a clustered environment you must deactivate a logical volume before it can be removed.

/dev/testvg/testlv from the volume group testvg. Note that in this case the logical volume has not been deactivated.

lvremove /dev/testvg/testlv Do you really want to remove active logical volume "testlv"? [y/n]: y Logical volume "testlv" successfully removed

# lvremove /dev/testvg/testlv

Do you really want to remove active logical volume "testlv"? [y/n]: y

Logical volume "testlv" successfully removed

lvchange -an command, in which case you would not see the prompt verifying whether you want to remove an active logical volume.

5.4.13. Displaying Logical Volumes

lvs, lvdisplay, and lvscan.

lvs command provides logical volume information in a configurable form, displaying one line per logical volume. The lvs command provides a great deal of format control, and is useful for scripting. For information on using the lvs command to customize your output, see Section 5.8, “Customized Reporting for LVM”.

lvdisplay command displays logical volume properties (such as size, layout, and mapping) in a fixed format.

lvol2 in vg00. If snapshot logical volumes have been created for this original logical volume, this command shows a list of all snapshot logical volumes and their status (active or inactive) as well.

lvdisplay -v /dev/vg00/lvol2

# lvdisplay -v /dev/vg00/lvol2lvscan command scans for all logical volumes in the system and lists them, as in the following example.

lvscan ACTIVE '/dev/vg0/gfslv' [1.46 GB] inherit

# lvscan

ACTIVE '/dev/vg0/gfslv' [1.46 GB] inherit

5.4.14. Growing Logical Volumes

lvextend command.

/dev/myvg/homevol to 12 gigabytes.

lvextend -L12G /dev/myvg/homevol lvextend -- extending logical volume "/dev/myvg/homevol" to 12 GB lvextend -- doing automatic backup of volume group "myvg" lvextend -- logical volume "/dev/myvg/homevol" successfully extended

# lvextend -L12G /dev/myvg/homevol

lvextend -- extending logical volume "/dev/myvg/homevol" to 12 GB

lvextend -- doing automatic backup of volume group "myvg"

lvextend -- logical volume "/dev/myvg/homevol" successfully extended

/dev/myvg/homevol.

lvextend -L+1G /dev/myvg/homevol lvextend -- extending logical volume "/dev/myvg/homevol" to 13 GB lvextend -- doing automatic backup of volume group "myvg" lvextend -- logical volume "/dev/myvg/homevol" successfully extended

# lvextend -L+1G /dev/myvg/homevol

lvextend -- extending logical volume "/dev/myvg/homevol" to 13 GB

lvextend -- doing automatic backup of volume group "myvg"

lvextend -- logical volume "/dev/myvg/homevol" successfully extended

lvcreate command, you can use the -l argument of the lvextend command to specify the number of extents by which to increase the size of the logical volume. You can also use this argument to specify a percentage of the volume group, or a percentage of the remaining free space in the volume group. The following command extends the logical volume called testlv to fill all of the unallocated space in the volume group myvg.

lvextend -l +100%FREE /dev/myvg/testlv Extending logical volume testlv to 68.59 GB Logical volume testlv successfully resized

# lvextend -l +100%FREE /dev/myvg/testlv

Extending logical volume testlv to 68.59 GB

Logical volume testlv successfully resized

5.4.14.1. Extending a Striped Volume

vg that consists of two underlying physical volumes, as displayed with the following vgs command.

vgs VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree vg 2 0 0 wz--n- 271.31G 271.31G

# vgs

VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree

vg 2 0 0 wz--n- 271.31G 271.31G

vgs VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree vg 2 1 0 wz--n- 271.31G 0

# vgs

VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree

vg 2 1 0 wz--n- 271.31G 0

lvextend command fails.

5.4.14.2. Extending a Mirrored Volume

lvextend command without performing a synchronization of the new mirror regions.

--nosync option when you create a mirrored logical volume with the lvcreate command, the mirror regions are not synchronized when the mirror is created, as described in Section 5.4.3, “Creating Mirrored Volumes”. If you later extend a mirror that you have created with the --nosync option, the mirror extensions are not synchronized at that time, either.

--nosync option by using the lvs command to display the volume's attributes. A logical volume will have an attribute bit 1 of "M" if it is a mirrored volume that was created without an initial synchronization, and it will have an attribute bit 1 of "m" if it was created with initial synchronization.