Planning, Installation, and Deployment Guide

Planning and installing Certificate System subsystems

Abstract

Part I. Planning how to deploy Red Hat Certificate System

This part provides an overview of Certificate System, including general PKI principles and specific features of Certificate System and its subsystems. Planning a deployment is vital to designing a PKI infrastructure that adequately meets the needs of your organization.

Chapter 1. Introduction to public-key cryptography

Public-key cryptography and related standards underlie the security features of many products such as signed and encrypted email, single sign-on, and Transport Layer Security/Secure Sockets Layer (SSL/TLS) communications. This chapter covers the basic concepts of public-key cryptography.

Internet traffic, which passes information through intermediate computers, can be intercepted by a third party:

- Eavesdropping

- Information remains intact, but its privacy is compromised. For example, someone could gather credit card numbers, record a sensitive conversation, or intercept classified information.

- Tampering

- Information in transit is changed or replaced and then sent to the recipient. For example, someone could alter an order for goods or change a person’s resume.

- Impersonation

Information passes to a person who poses as the intended recipient. Impersonation can take two forms:

-

Spoofing. A person can pretend to be someone else. For example, a person can pretend to have the email address

jdoe@example.netor a computer can falsely identify itself as a site calledwww.example.net. -

Misrepresentation. A person or organization can misrepresent itself. For example, a site called

www.example.netcan purport to be an on-line furniture store when it really receives credit-card payments but never sends any goods. Public-key cryptography provides protection against Internet-based attacks through:

-

Spoofing. A person can pretend to be someone else. For example, a person can pretend to have the email address

- Encryption and decryption

- Encryption and decryption allow two communicating parties to disguise information they send to each other. The sender encrypts, or scrambles, information before sending it. The receiver decrypts, or unscrambles, the information after receiving it. While in transit, the encrypted information is unintelligible to an intruder.

- Tamper detection

- Tamper detection allows the recipient of information to verify that it has not been modified in transit. Any attempts to modify or substitute data are detected.

- Authentication

- Authentication allows the recipient of information to determine its origin by confirming the sender’s identity.

- Nonrepudiation

- Nonrepudiation prevents the sender of information from claiming at a later date that the information was never sent.

1.1. Encryption and decryption

Encryption is the process of transforming information so it is unintelligible to anyone but the intended recipient. Decryption is the process of decoding encrypted information. A cryptographic algorithm, also called a cipher, is a mathematical function used for encryption or decryption. Usually, two related functions are used, one for encryption and the other for decryption.

With most modern cryptography, the ability to keep encrypted information secret is based not on the cryptographic algorithm, which is widely known, but on a number called a key that must be used with the algorithm to produce an encrypted result or to decrypt previously encrypted information. Decryption with the correct key is simple. Decryption without the correct key is very difficult, if not impossible.

1.1.1. Symmetric-key encryption

With symmetric-key encryption, the encryption key can be calculated from the decryption key and vice versa. With most symmetric algorithms, the same key is used for both encryption and decryption, as shown in Figure 1.1, “Symmetric-key encryption”.

Figure 1.1. Symmetric-key encryption

Implementations of symmetric-key encryption can be highly efficient, so that users do not experience any significant time delay as a result of the encryption and decryption.

Symmetric-key encryption is effective only if the symmetric key is kept secret by the two parties involved. If anyone else discovers the key, it affects both confidentiality and authentication. A person with an unauthorized symmetric key not only can decrypt messages sent with that key, but can encrypt new messages and send them as if they came from one of the legitimate parties using the key.

Symmetric-key encryption plays an important role in SSL/TLS communication, which is widely used for authentication, tamper detection, and encryption over TCP/IP networks. SSL/TLS also uses techniques of public-key encryption, which is described in the next section.

1.1.2. Public-key encryption

Public-key encryption (also called asymmetric encryption) involves a pair of keys, a public key and a private key, associated with an entity. Each public key is published, and the corresponding private key is kept secret. (For more information about the way public keys are published, see Section 1.3, “Certificates and authentication”.) Data encrypted with a public key can be decrypted only with the corresponding private key. Figure 1.2, “Public-key encryption” shows a simplified view of the way public-key encryption works.

Figure 1.2. Public-key encryption

The scheme shown in Figure 1.2, “Public-key encryption” allows public keys to be freely distributed, while only authorized people are able to read data encrypted using this key. In general, to send encrypted data, the data is encrypted with that person’s public key, and the person receiving the encrypted data decrypts it with the corresponding private key.

Compared with symmetric-key encryption, public-key encryption requires more processing and may not be feasible for encrypting and decrypting large amounts of data. However, it is possible to use public-key encryption to send a symmetric key, which can then be used to encrypt additional data. This is the approach used by the SSL/TLS protocols.

The reverse of the scheme shown in Figure 1.2, “Public-key encryption” also works: data encrypted with a private key can be decrypted only with the corresponding public key. This is not a recommended practice to encrypt sensitive data, however, because it means that anyone with the public key, which is by definition published, could decrypt the data. Nevertheless, private-key encryption is useful because it means the private key can be used to sign data with a digital signature, an important requirement for electronic commerce and other commercial applications of cryptography. Client software such as Mozilla Firefox can then use the public key to confirm that the message was signed with the appropriate private key and that it has not been tampered with since being signed. Section 1.2, “Digital signatures” illustrates how this confirmation process works.

1.1.3. Key length and encryption strength

Breaking an encryption algorithm is finding the key to the access the encrypted data in plain text. For symmetric algorithms, breaking the algorithm usually means trying to determine the key used to encrypt the text. For a public key algorithm, breaking the algorithm usually means acquiring the shared secret information between two recipients.

One method of breaking a symmetric algorithm is to simply try every key within the full algorithm until the right key is found. For public key algorithms, since half of the key pair is publicly known, the other half (private key) can be derived using published, though complex, mathematical calculations. Manually finding the key to break an algorithm is called a brute force attack.

Breaking an algorithm introduces the risk of intercepting, or even impersonating and fraudulently verifying, private information.

The key strength of an algorithm is determined by finding the fastest method to break the algorithm and comparing it to a brute force attack.

For symmetric keys, encryption strength is often described in terms of the size or length of the keys used to perform the encryption: longer keys generally provide stronger encryption. Key length is measured in bits.

An encryption key is considered full strength if the best known attack to break the key is no faster than a brute force attempt to test every key possibility.

Different types of algorithms -particularly public key algorithms -may require different key lengths to achieve the same level of encryption strength as a symmetric-key cipher. The RSA cipher can use only a subset of all possible values for a key of a given length, due to the nature of the mathematical problem on which it is based. Other ciphers, such as those used for symmetric-key encryption, can use all possible values for a key of a given length. More possible matching options means more security.

Because it is relatively trivial to break an RSA key, an RSA public-key encryption cipher must have a very long key -at least 2048 bits -to be considered cryptographically strong. On the other hand, symmetric-key ciphers are reckoned to be equivalently strong using a much shorter key length, as little as 80 bits for most algorithms. Similarly, public-key ciphers based on the elliptic curve cryptography (ECC), such as the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) ciphers, also require less bits than RSA ciphers.

1.2. Digital signatures

Tamper detection relies on a mathematical function called a one-way hash (also called a message digest). A one-way hash is a number of fixed length with the following characteristics:

- The value of the hash is unique for the hashed data. Any change in the data, even deleting or altering a single character, results in a different value.

- The content of the hashed data cannot be deduced from the hash.

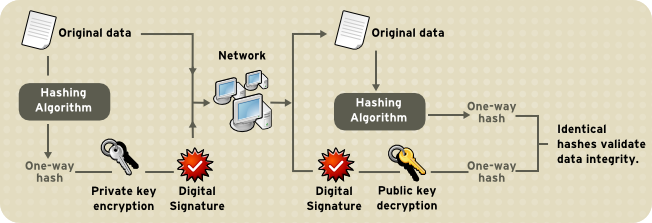

As mentioned in Section 1.1.2, “Public-key encryption”, it is possible to use a private key for encryption and the corresponding public key for decryption. Although not recommended when encrypting sensitive information, it is a crucial part of digitally signing any data. Instead of encrypting the data itself, the signing software creates a one-way hash of the data, then uses the private key to encrypt the hash. The encrypted hash, along with other information such as the hashing algorithm, is known as a digital signature.

Figure 1.3, “Using a digital signature to validate data integrity” illustrates the way a digital signature can be used to validate the integrity of signed data.

Figure 1.3. Using a digital signature to validate data integrity

Figure 1.3, “Using a digital signature to validate data integrity” shows two items transferred to the recipient of some signed data: the original data and the digital signature, which is a one-way hash of the original data encrypted with the signer’s private key. To validate the integrity of the data, the receiving software first uses the public key to decrypt the hash. It then uses the same hashing algorithm that generated the original hash to generate a new one-way hash of the same data. (Information about the hashing algorithm used is sent with the digital signature.) Finally, the receiving software compares the new hash against the original hash. If the two hashes match, the data has not changed since it was signed. If they do not match, the data may have been tampered with since it was signed, or the signature may have been created with a private key that does not correspond to the public key presented by the signer.

If the two hashes match, the recipient can be certain that the public key used to decrypt the digital signature corresponds to the private key used to create the digital signature. Confirming the identity of the signer also requires some way of confirming that the public key belongs to a particular entity. For more information on authenticating users, see Section 1.3, “Certificates and authentication”.

A digital signature is similar to a handwritten signature. Once data have been signed, it is difficult to deny doing so later, assuming the private key has not been compromised. This quality of digital signatures provides a high degree of nonrepudiation; digital signatures make it difficult for the signer to deny having signed the data. In some situations, a digital signature is as legally binding as a handwritten signature.

1.3. Certificates and authentication

1.3.1. A certificate identifies someone or something

A certificate is an electronic document used to identify an individual, a server, a company, or other entity and to associate that identity with a public key. Like a driver’s license or passport, a certificate provides generally recognized proof of a person’s identity. Public-key cryptography uses certificates to address the problem of impersonation.

To get personal ID such as a driver’s license, a person has to present some other form of identification which confirms that the person is who he claims to be. Certificates work much the same way. Certificate authorities (CAs) validate identities and issue certificates. CAs can be either independent third parties or organizations running their own certificate-issuing server software, such as Certificate System. The methods used to validate an identity vary depending on the policies of a given CA for the type of certificate being requested. Before issuing a certificate, a CA must confirm the user’s identity with its standard verification procedures.

The certificate issued by the CA binds a particular public key to the name of the entity the certificate identifies, such as the name of an employee or a server. Certificates help prevent the use of fake public keys for impersonation. Only the public key certified by the certificate will work with the corresponding private key possessed by the entity identified by the certificate.

In addition to a public key, a certificate always includes the name of the entity it identifies, an expiration date, the name of the CA that issued the certificate, and a serial number. Most importantly, a certificate always includes the digital signature of the issuing CA. The CA’s digital signature allows the certificate to serve as a valid credential for users who know and trust the CA but do not know the entity identified by the certificate.

For more information about the role of CAs, see Section 1.3.6, “How CA certificates establish trust”.

1.3.2. Authentication confirms an identity

Authentication is the process of confirming an identity. For network interactions, authentication involves the identification of one party by another party. There are many ways to use authentication over networks. Certificates are one of those way.

Network interactions typically take place between a client, such as a web browser, and a server. Client authentication refers to the identification of a client (the person assumed to be using the software) by a server. Server authentication refers to the identification of a server (the organization assumed to be running the server at the network address) by a client.

Client and server authentication are not the only forms of authentication that certificates support. For example, the digital signature on an email message, combined with the certificate that identifies the sender, can authenticate the sender of the message. Similarly, a digital signature on an HTML form, combined with a certificate that identifies the signer, can provide evidence that the person identified by that certificate agreed to the contents of the form. In addition to authentication, the digital signature in both cases ensures a degree of nonrepudiation; a digital signature makes it difficult for the signer to claim later not to have sent the email or the form.

Client authentication is an essential element of network security within most intranets or extranets. There are two main forms of client authentication:

- Password-based authentication

- Almost all server software permits client authentication by requiring a recognized name and password before granting access to the server.

- Certificate-based authentication

- Client authentication based on certificates is part of the SSL/TLS protocol. The client digitally signs a randomly generated piece of data and sends both the certificate and the signed data across the network. The server validates the signature and confirms the validity of the certificate.

1.3.2.1. Password-based authentication

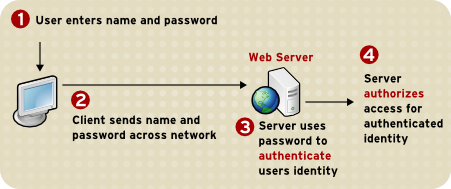

Figure 1.4, “Using a password to authenticate a client to a server” shows the process of authenticating a user using a user name and password. This example assumes the following:

- The user has already trusted the server, either without authentication or on the basis of server authentication over SSL/TLS.

- The user has requested a resource controlled by the server.

- The server requires client authentication before permitting access to the requested resource.

Figure 1.4. Using a password to authenticate a client to a server

These are the steps in this authentication process:

- When the server requests authentication from the client, the client displays a dialog box requesting the user name and password for that server.

- The client sends the name and password across the network, either in plain text or over an encrypted SSL/TLS connection.

- The server looks up the name and password in its local password database and, if they match, accepts them as evidence authenticating the user’s identity.

- The server determines whether the identified user is permitted to access the requested resource and, if so, allows the client to access it.

With this arrangement, the user must supply a new password for each server accessed, and the administrator must keep track of the name and password for each user.

1.3.2.2. Certificate-based authentication

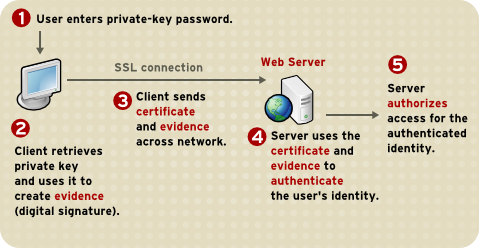

One of the advantages of certificate-based authentication is that it can be used to replace the first three steps in authentication with a mechanism that allows the user to supply one password, which is not sent across the network, and allows the administrator to control user authentication centrally. This is called single sign-on.

Figure 1.5, “Using a certificate to authenticate a client to a server” shows how client authentication works using certificates and SSL/TLS. To authenticate a user to a server, a client digitally signs a randomly generated piece of data and sends both the certificate and the signed data across the network. The server authenticates the user’s identity based on the data in the certificate and signed data.

Like Figure 1.4, “Using a password to authenticate a client to a server”, Figure 1.5, “Using a certificate to authenticate a client to a server” assumes that the user has already trusted the server and requested a resource and that the server has requested client authentication before granting access to the requested resource.

Figure 1.5. Using a certificate to authenticate a client to a server

Unlike the authentication process in Figure 1.4, “Using a password to authenticate a client to a server”, the authentication process in Figure 1.5, “Using a certificate to authenticate a client to a server” requires SSL/TLS. Figure 1.5, “Using a certificate to authenticate a client to a server” also assumes that the client has a valid certificate that can be used to identify the client to the server. Certificate-based authentication is preferred to password-based authentication because it is based on the user both possessing the private key and knowing the password. However, these two assumptions are true only if unauthorized personnel have not gained access to the user’s machine or password, the password for the client software’s private key database has been set, and the software is set up to request the password at reasonably frequent intervals.

Neither password-based authentication nor certificate-based authentication address security issues related to physical access to individual machines or passwords. Public-key cryptography can only verify that a private key used to sign some data corresponds to the public key in a certificate. It is the user’s responsibility to protect a machine’s physical security and to keep the private-key password secret.

These are the authentication steps shown in Figure 1.5, “Using a certificate to authenticate a client to a server”:

The client software maintains a database of the private keys that correspond to the public keys published in any certificates issued for that client. The client asks for the password to this database the first time the client needs to access it during a given session, such as the first time the user attempts to access an SSL/TLS-enabled server that requires certificate-based client authentication.

After entering this password once, the user does not need to enter it again for the rest of the session, even when accessing other SSL/TLS-enabled servers.

- The client unlocks the private-key database, retrieves the private key for the user’s certificate, and uses that private key to sign data randomly-generated from input from both the client and the server. This data and the digital signature are evidence of the private key’s validity. The digital signature can be created only with that private key and can be validated with the corresponding public key against the signed data, which is unique to the SSL/TLS session.

- The client sends both the user’s certificate and the randomly-generated data across the network.

- The server uses the certificate and the signed data to authenticate the user’s identity.

- The server may perform other authentication tasks, such as checking that the certificate presented by the client is stored in the user’s entry in an LDAP directory. The server then evaluates whether the identified user is permitted to access the requested resource. This evaluation process can employ a variety of standard authorization mechanisms, potentially using additional information in an LDAP directory or company databases. If the result of the evaluation is positive, the server allows the client to access the requested resource.

Certificates replace the authentication portion of the interaction between the client and the server. Instead of requiring a user to send passwords across the network continually, single sign-on requires the user to enter the private-key database password once, without sending it across the network. For the rest of the session, the client presents the user’s certificate to authenticate the user to each new server it encounters. Existing authorization mechanisms based on the authenticated user identity are not affected.

1.3.3. Uses for certificates

The purpose of certificates is to establish trust. Their usage varies depending on the kind of trust they are used to ensure. Some kinds of certificates are used to verify the identity of the presenter; others are used to verify that an object or item has not been tampered with.

1.3.3.1. SSL/TLS

The Transport Layer Security/Secure Sockets Layer (SSL/TLS) protocol governs server authentication, client authentication, and encrypted communication between servers and clients. SSL/TLS is widely used on the Internet, especially for interactions that involve exchanging confidential information such as credit card numbers.

SSL/TLS requires an SSL/TLS server certificate. As part of the initial SSL/TLS handshake, the server presents its certificate to the client to authenticate the server’s identity. The authentication uses public-key encryption and digital signatures to confirm that the server is the server it claims to be. Once the server has been authenticated, the client and server use symmetric-key encryption, which is very fast, to encrypt all the information exchanged for the remainder of the session and to detect any tampering.

Servers may be configured to require client authentication as well as server authentication. In this case, after server authentication is successfully completed, the client must also present its certificate to the server to authenticate the client’s identity before the encrypted SSL/TLS session can be established.

For an overview of client authentication over SSL/TLS and how it differs from password-based authentication, see Section 1.3.2, “Authentication confirms an identity”.

1.3.3.2. Signed and encrypted email

Some email programs support digitally signed and encrypted email using a widely accepted protocol known as Secure Multipurpose Internet Mail Extension (S/MIME). Using S/MIME to sign or encrypt email messages requires the sender of the message to have an S/MIME certificate.

An email message that includes a digital signature provides some assurance that it was sent by the person whose name appears in the message header, thus authenticating the sender. If the digital signature cannot be validated by the email software, the user is alerted.

The digital signature is unique to the message it accompanies. If the message received differs in any way from the message that was sent, even by adding or deleting a single character, the digital signature cannot be validated. Therefore, signed email also provides assurance that the email has not been tampered with. This kind of assurance is known as nonrepudiation, which makes it difficult for the sender to deny having sent the message. This is important for business communication. For information about the way digital signatures work, see Section 1.2, “Digital signatures”.

S/MIME also makes it possible to encrypt email messages, which is important for some business users. However, using encryption for email requires careful planning. If the recipient of encrypted email messages loses the private key and does not have access to a backup copy of the key, the encrypted messages can never be decrypted.

1.3.3.3. Single sign-on

Network users are frequently required to remember multiple passwords for the various services they use. For example, a user might have to type a different password to log into the network, collect email, use directory services, use the corporate calendar program, and access various servers. Multiple passwords are an ongoing headache for both users and system administrators. Users have difficulty keeping track of different passwords, tend to choose poor ones, and tend to write them down in obvious places. Administrators must keep track of a separate password database on each server and deal with potential security problems related to the fact that passwords are sent over the network routinely and frequently.

Solving this problem requires some way for a user to log in once, using a single password, and get authenticated access to all network resources that user is authorized to use-without sending any passwords over the network. This capability is known as single sign-on.

Both client SSL/TLS certificates and S/MIME certificates can play a significant role in a comprehensive single sign-on solution. For example, one form of single sign-on supported by Red Hat products relies on SSL/TLS client authentication. A user can log in once, using a single password to the local client’s private-key database, and get authenticated access to all SSL/TLS-enabled servers that user is authorized to use-without sending any passwords over the network. This approach simplifies access for users, because they do not need to enter passwords for each new server. It also simplifies network management, since administrators can control access by controlling lists of certificate authorities (CAs) rather than much longer lists of users and passwords.

In addition to using certificates, a complete single-sign on solution must address the need to interoperate with enterprise systems, such as the underlying operating system, that rely on passwords or other forms of authentication.

1.3.3.4. Object signing

Many software technologies support a set of tools called object signing. Object signing uses standard techniques of public-key cryptography to let users get reliable information about code they download in much the same way they can get reliable information about shrink-wrapped software.

Most important, object signing helps users and network administrators implement decisions about software distributed over intranets or the Internet-for example, whether to allow Java applets signed by a given entity to use specific computer capabilities on specific users' machines.

The objects signed with object signing technology can be applets or other Java code, JavaScript scripts, plug-ins, or any kind of file. The signature is a digital signature. Signed objects and their signatures are typically stored in a special file called a JAR file.

Software developers and others who wish to sign files using object-signing technology must first obtain an object-signing certificate.

1.3.4. Types of Certificates

The Certificate System is capable of generating different types of certificates for different uses and in different formats. Planning which certificates are required and planning how to manage them, including determining what formats are needed and how to plan for renewal, are important to manage both the PKI and the Certificate System instances.

This list is not exhaustive; there are certificate enrollment forms for dual-use certificates for LDAP directories, file-signing certificates, and other subsystem certificates. These forms are available through the Certificate Manager’s end-entities page, at ui`8443/ca/ee/ca`.

When the different Certificate System subsystems are installed, the basic required certificates and keys are generated; for example, configuring the Certificate Manager generates the CA signing certificate for the self-signed root CA and the internal OCSP signing, audit signing, SSL/TLS server, and agent user certificates. During the KRA configuration, the Certificate Manager generates the storage, transport, audit signing, and agent certificates. Additional certificates can be created and installed separately.

| Certificate Type | Use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Client SSL/TLS certificates | Used for client authentication to servers over SSL/TLS. Typically, the identity of the client is assumed to be the same as the identity of a person, such as an employee. See Section 1.3.2.2, “Certificate-based authentication” for a description of the way SSL/TLS client certificates are used for client authentication. Client SSL/TLS certificates can also be used as part of single sign-on. | A bank gives a customer an SSL/TLS client certificate that allows the bank’s servers to identify that customer and authorize access to the customer’s accounts. A company gives a new employee an SSL/TLS client certificate that allows the company’s servers to identify that employee and authorize access to the company’s servers. |

| Server SSL/TLS certificates | Used for server authentication to clients over SSL/TLS. Server authentication may be used without client authentication. Server authentication is required for an encrypted SSL/TLS session. For more information, see Section 1.3.3.1, “SSL/TLS”. | Internet sites that engage in electronic commerce usually support certificate-based server authentication to establish an encrypted SSL/TLS session and to assure customers that they are dealing with the web site identified with the company. The encrypted SSL/TLS session ensures that personal information sent over the network, such as credit card numbers, cannot easily be intercepted. |

| S/MIME certificates | Used for signed and encrypted email. As with SSL/TLS client certificates, the identity of the client is assumed to be the same as the identity of a person, such as an employee. A single certificate may be used as both an S/MIME certificate and an SSL/TLS certificate; see Section 1.3.3.2, “Signed and encrypted email”. S/MIME certificates can also be used as part of single sign-on. | A company deploys combined S/MIME and SSL/TLS certificates solely to authenticate employee identities, thus permitting signed email and SSL/TLS client authentication but not encrypted email. Another company issues S/MIME certificates solely to sign and encrypt email that deals with sensitive financial or legal matters. |

| CA certificates | Used to identify CAs. Client and server software use CA certificates to determine what other certificates can be trusted. For more information, see Section 1.3.6, “How CA certificates establish trust”. | The CA certificates stored in Mozilla Firefox determine what other certificates can be authenticated. An administrator can implement corporate security policies by controlling the CA certificates stored in each user’s copy of Firefox. |

| Object-signing certificates | Used to identify signers of Java code, JavaScript scripts, or other signed files. | Software companies frequently sign software distributed over the Internet to provide users with some assurance that the software is a legitimate product of that company. Using certificates and digital signatures can also make it possible for users to identify and control the kind of access downloaded software has to their computers. |

1.3.4.1. CA signing certificates

Every Certificate Manager has a CA signing certificate with a public/private key pair it uses to sign the certificates and certificate revocation lists (CRLs) it issues. This certificate is created and installed when the Certificate Manager is installed.

For more information about CRLs, see Section 2.4.4, “Revoking certificates and checking status”.

The Certificate Manager’s status as a root or subordinate CA is determined by whether its CA signing certificate is self-signed or is signed by another CA. Self-signed root CAs set the policies they use to issue certificates, such as the subject names, types of certificates that can be issued, and to whom certificates can be issued. A subordinate CA has a CA signing certificate signed by another CA, usually the one that is a level above in the CA hierarchy (which may or may not be a root CA). If the Certificate Manager is a subordinate CA in a CA hierarchy, the root CA’s signing certificate must be imported into individual clients and servers before the Certificate Manager can be used to issue certificates to them.

The CA certificate must be installed in a client if a server or user certificate issued by that CA is installed on that client. The CA certificate confirms that the server certificate can be trusted. Ideally, the certificate chain is installed.

1.3.4.2. Other signing certificates

Other services, such as the Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) responder service and CRL publishing, can use signing certificates other than the CA certificate. For example, a separate CRL signing certificate can be used to sign the revocation lists that are published by a CA instead of using the CA signing certificate.

For more information about OCSP, see Section 2.4.4, “Revoking certificates and checking status”.

1.3.4.3. SSL/TLS server and client certificates

Server certificates are used for secure communications, such as SSL/TLS, and other secure functions. Server certificates are used to authenticate themselves during operations and to encrypt data; client certificates authenticate the client to the server.

CAs which have a signing certificate issued by a third-party may not be able to issue server certificates. The third-party CA may have rules in place which prohibit its subordinates from issuing server certificates.

1.3.4.4. User certificates

End user certificates are a subset of client certificates that are used to identify users to a server or system. Users can be assigned certificates to use for secure communications, such as SSL/TLS, and other functions such as encrypting email or for single sign-on. Special users, such as Certificate System agents, can be given client certificates to access special services.

1.3.4.5. Dual-key pairs

Dual-key pairs are a set of two private and public keys, where one set is used for signing and one for encryption. These dual keys are used to create dual certificates. The dual certificate enrollment form is one of the standard forms listed in the end-entities page of the Certificate Manager.

When generating dual-key pairs, set the certificate profiles to work correctly when generating separate certificates for signing and encryption.

1.3.4.6. Cross-pair certificates

The Certificate System can issue, import, and publish cross-pair CA certificates. With cross-pair certificates, one CA signs and issues a cross-pair certificate to a second CA, and the second CA signs and issues a cross-pair certificate to the first CA. Both CAs then store or publish both certificates as a crossCertificatePair entry.

Bridging certificates can be done to honor certificates issued by a CA that is not chained to the root CA. By establishing a trust between the Certificate System CA and another CA through a cross-pair CA certificate, the cross-pair certificate can be downloaded and used to trust the certificates issued by the other CA.

1.3.5. Contents of a certificate

The contents of certificates are organized according to the X.509 v3 certificate specification, which has been recommended by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), an international standards body.

Users do not usually need to be concerned about the exact contents of a certificate. However, system administrators working with certificates may need some familiarity with the information contained in them.

1.3.5.1. Certificate data formats

Certificate requests and certificates can be created, stored, and installed in several different formats. All of these formats conform to X.509 standards.

1.3.5.1.1. Binary

The following binary formats are recognized:

- DER-encoded certificate. This is a single binary DER-encoded certificate.

-

PKCS #7 certificate chain. This is a PKCS #7

SignedDataobject. The only significant field in theSignedDataobject is the certificates; the signature and the contents, for example, are ignored. The PKCS #7 format allows multiple certificates to be downloaded at a single time. Netscape Certificate Sequence. This is a simpler format for downloading certificate chains in a PKCS #7

ContentInfostructure, wrapping a sequence of certificates. The value of thecontentTypefield should benetscape-cert-sequence, while the content field has the following structure:CertificateSequence ::= SEQUENCE OF Certificate

CertificateSequence ::= SEQUENCE OF CertificateCopy to Clipboard Copied! Toggle word wrap Toggle overflow This format allows multiple certificates to be downloaded at the same time.

1.3.5.1.2. Text

Any of the binary formats can be imported in text form. The text form begins with the following line:

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----Following this line is the certificate data, which can be in any of the binary formats described. This data should be base-64 encoded, as described by RFC 1113. The certificate information is followed by this line:

-----END CERTIFICATE-----

-----END CERTIFICATE-----1.3.5.2. Distinguished names

An X.509 v3 certificate binds a distinguished name (DN) to a public key. A DN is a series of name-value pairs, such as uid=doe, that uniquely identify an entity. This is also called the certificate subject name.

This is an example DN of an employee for Example Corp.:

uid=doe,cn=John Doe,o=Example Corp.,c=US

uid=doe,cn=John Doe,o=Example Corp.,c=US

In this DN, uid is the user name, cn is the user’s common name, o is the organization or company name, and c is the country.

DNs may include a variety of other name-value pairs. They are used to identify both certificate subjects and entries in directories that support the Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP).

The rules governing the construction of DNs can be complex; for comprehensive information about DNs, see A String Representation of Distinguished Names at http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc4514.txt.

1.3.5.3. A typical certificate

Every X.509 certificate consists of two sections:

- The data section

This section includes the following information:

- The version number of the X.509 standard supported by the certificate.

- The certificate’s serial number. Every certificate issued by a CA has a serial number that is unique among the certificates issued by that CA.

- Information about the user’s public key, including the algorithm used and a representation of the key itself.

- The DN of the CA that issued the certificate.

- The period during which the certificate is valid; for example, between 1:00 p.m. on November 15, 2004, and 1:00 p.m. November 15, 2022.

- The DN of the certificate subject, which is also called the subject name; for example, in an SSL/TLS client certificate, this is the user’s DN.

Optional certificate extensions, which may provide additional data used by the client or server. For example:

- the Netscape Certificate Type extension indicates the type of certificate, such as an SSL/TLS client certificate, an SSL/TLS server certificate, or a certificate for signing email

- the Subject Alternative Name (SAN) extension links a certificate to one or more host names

Certificate extensions can also be used for other purposes.

- The signature section

This section includes the following information:

- The cryptographic algorithm, or cipher, used by the issuing CA to create its own digital signature.

- The CA’s digital signature, obtained by hashing all of the data in the certificate together and encrypting it with the CA’s private key. Here are the data and signature sections of a certificate shown in the readable pretty-print format:

Here is the same certificate in the base-64 encoded format:

1.3.6. How CA certificates establish trust

CAs validate identities and issue certificates. They can be either independent third parties or organizations running their own certificate-issuing server software, such as the Certificate System.

Any client or server software that supports certificates maintains a collection of trusted CA certificates. These CA certificates determine which issuers of certificates the software can trust, or validate. In the simplest case, the software can validate only certificates issued by one of the CAs for which it has a certificate. It is also possible for a trusted CA certificate to be part of a chain of CA certificates, each issued by the CA above it in a certificate hierarchy.

The sections that follow explains how certificate hierarchies and certificate chains determine what certificates software can trust.

1.3.6.1. CA hierarchies

In large organizations, responsibility for issuing certificates can be delegated to several different CAs. For example, the number of certificates required may be too large for a single CA to maintain; different organizational units may have different policy requirements; or a CA may need to be physically located in the same geographic area as the people to whom it is issuing certificates.

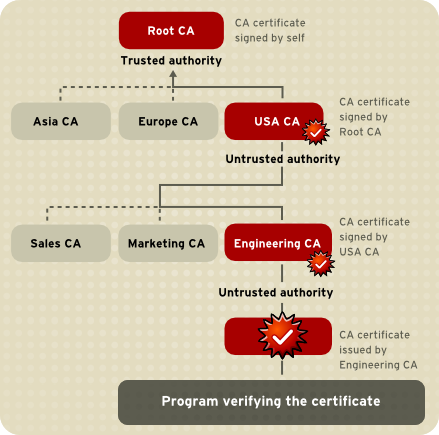

These certificate-issuing responsibilities can be divided among subordinate CAs. The X.509 standard includes a model for setting up a hierarchy of CAs, shown in Figure 1.6, “Example of a hierarchy of certificate authorities”.

Figure 1.6. Example of a hierarchy of certificate authorities

The root CA is at the top of the hierarchy. The root CA’s certificate is a self-signed certificate; that is, the certificate is digitally signed by the same entity that the certificate identifies. The CAs that are directly subordinate to the root CA have CA certificates signed by the root CA. CAs under the subordinate CAs in the hierarchy have their CA certificates signed by the higher-level subordinate CAs.

Organizations have a great deal of flexibility in how CA hierarchies are set up; Figure 1.6, “Example of a hierarchy of certificate authorities” shows just one example.

1.3.6.2. Certificate chains

CA hierarchies are reflected in certificate chains. A certificate chain is series of certificates issued by successive CAs. Figure 1.7, “Example of a certificate chain” shows a certificate chain leading from a certificate that identifies an entity through two subordinate CA certificates to the CA certificate for the root CA, based on the CA hierarchy shown in Figure 1.6, “Example of a hierarchy of certificate authorities”.

Figure 1.7. Example of a certificate chain

A certificate chain traces a path of certificates from a branch in the hierarchy to the root of the hierarchy. In a certificate chain, the following occur:

- Each certificate is followed by the certificate of its issuer.

Each certificate contains the name (DN) of that certificate’s issuer, which is the same as the subject name of the next certificate in the chain.

In Figure 1.7, “Example of a certificate chain”, the

Engineering CAcertificate contains the DN of the CA,USA CA, that issued that certificate.USA CA's DN is also the subject name of the next certificate in the chain.Each certificate is signed with the private key of its issuer. The signature can be verified with the public key in the issuer’s certificate, which is the next certificate in the chain.

In Figure 1.7, “Example of a certificate chain”, the public key in the certificate for the

USA CAcan be used to verify theUSA CA's digital signature on the certificate for theEngineering CA.

1.3.6.3. Verifying a certificate chain

Certificate chain verification makes sure a given certificate chain is well-formed, valid, properly signed, and trustworthy. The following description of the process covers the most important steps of forming and verifying a certificate chain, starting with the certificate being presented for authentication:

- The certificate validity period is checked against the current time provided by the verifier’s system clock.

- The issuer’s certificate is located. The source can be either the verifier’s local certificate database on that client or server or the certificate chain provided by the subject, as with an SSL/TLS connection.

- The certificate signature is verified using the public key in the issuer’s certificate.

- The host name of the service is compared against the Subject Alternative Name (SAN) extension. If the certificate has no such extension, the host name is compared against the subject’s CN.

- The system verifies the Basic Constraint requirements for the certificate, that is, whether the certificate is a CA and how many subsidiaries it is allowed to sign.

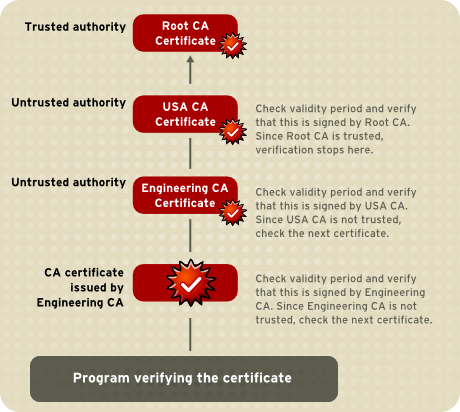

- If the issuer’s certificate is trusted by the verifier in the verifier’s certificate database, verification stops successfully here. Otherwise, the issuer’s certificate is checked to make sure it contains the appropriate subordinate CA indication in the certificate type extension, and chain verification starts over with this new certificate. Figure 1.8, “Verifying a certificate chain to the root CA” presents an example of this process.

Figure 1.8. Verifying a certificate chain to the root CA

Figure 1.8, “Verifying a certificate chain to the root CA” illustrates what happens when only the root CA is included in the verifier’s local database. If a certificate for one of the intermediate CAs, such as Engineering CA, is found in the verifier’s local database, verification stops with that certificate, as shown in Figure 1.9, “Verifying a certificate chain to an intermediate CA”.

Figure 1.9. Verifying a certificate chain to an intermediate CA

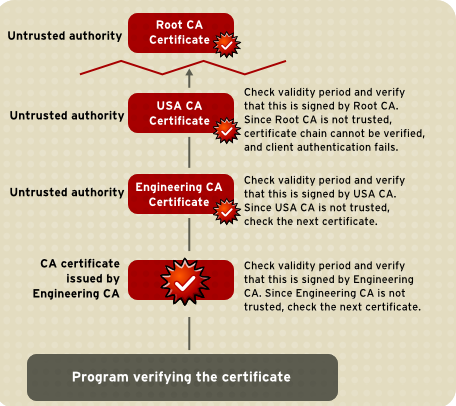

Expired validity dates, an invalid signature, or the absence of a certificate for the issuing CA at any point in the certificate chain causes authentication to fail. Figure 1.10, “A certificate chain that cannot be verified” shows how verification fails if neither the root CA certificate nor any of the intermediate CA certificates are included in the verifier’s local database.

Figure 1.10. A certificate chain that cannot be verified

1.3.7. Certificate status

For more information on Certificate Revocation List (CRL), see Section 2.4.4.2.1, “CRLs”

For more information on Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP), see Section 2.4.4.2.2, “OCSP services”

1.4. Certificate life cycle

Certificates are used in many applications, from encrypting email to accessing websites. There are two major stages in the lifecycle of the certificate: the point when it is issued (issuance and enrollment) and the period when the certificates are no longer valid (renewal or revocation). There are also ways to manage the certificate during its cycle. Making information about the certificate available to other applications is publishing the certificate and then backing up the key pairs so that the certificate can be recovered if it is lost.

1.4.1. Certificate issuance

The process for issuing a certificate depends on the CA that issues it and the purpose for which it will be used. Issuing non-digital forms of identification varies in similar ways. The requirements to get a library card are different than the ones to get a driver’s license. Similarly, different CAs have different procedures for issuing different kinds of certificates. Requirements for receiving a certificate can be as simple as an email address or user name and password to notarized documents, a background check, and a personal interview.

Depending on an organization’s policies, the process of issuing certificates can range from being completely transparent for the user to requiring significant user participation and complex procedures. In general, processes for issuing certificates should be flexible, so organizations can tailor them to their changing needs.

1.4.2. Certificate expiration and renewal

Like a driver’s license, a certificate specifies a period of time during which it is valid. Attempts to use a certificate for authentication before or after its validity period will fail. Managing certificate expirations and renewals are an essential part of the certificate management strategy. For example, an administrator may wish to be notified automatically when a certificate is about to expire so that an appropriate renewal process can be completed without disrupting the system operation. The renewal process may involve reusing the same public-private key pair or issuing a new one.

Additionally, it may be necessary to revoke a certificate before it has expired, such as when an employee leaves a company or moves to a new job in a different unit within the company.

Certificate revocation can be handled in several different ways:

- Verify if the certificate is present in the directory

- Servers can be configured so that the authentication process checks the directory for the presence of the certificate being presented. When an administrator revokes a certificate, the certificate can be automatically removed from the directory, and subsequent authentication attempts with that certificate will fail, even though the certificate remains valid in every other respect.

- Certificate revocation list (CRL)

- A list of revoked certificates, a CRL, can be published to the directory at regular intervals. The CRL can be checked as part of the authentication process.

- Real-time status checking

- The issuing CA can also be checked directly each time a certificate is presented for authentication. This procedure is sometimes called real-time status checking.

- Online Certificate Status Protocol

- The Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) service can be configured to determine the status of certificates.

For more information about renewing certificates, see Section 2.4.2, “Renewing certificates”. For more information about revoking certificates, including CRLs and OCSP, see Section 2.4.4, “Revoking certificates and checking status”.

1.5. Key management

Before a certificate can be issued, the public key it contains and the corresponding private key must be generated. Sometimes it may be useful to issue a single person one certificate and key pair for signing operations and another certificate and key pair for encryption operations. Separate signing and encryption certificates keep the private signing key only on the local machine, providing maximum nonrepudiation. This also aids in backing up the private encryption key in some central location where it can be retrieved in case the user loses the original key or leaves the company.

Keys can be generated by client software or generated centrally by the CA and distributed to users through an LDAP directory. There are costs associated with either method. Local key generation provides maximum nonrepudiation but may involve more participation by the user in the issuing process. Flexible key management capabilities are essential for most organizations.

Key recovery , or the ability to retrieve backups of encryption keys under carefully defined conditions, can be a crucial part of certificate management, depending on how an organization uses certificates. In some PKI setups, several authorized personnel must agree before an encryption key can be recovered to ensure that the key is only recovered to the legitimate owner in authorized circumstance. It can be necessary to recover a key when information is encrypted and can only be decrypted by the lost key.

Chapter 2. Introduction to Red Hat Certificate System

Every common PKI operation, such as issuing, renewing, and revoking certificates; archiving and recovering keys; publishing CRLs and verifying certificate status, is carried out by interoperating subsystems within Red Hat Certificate System. The functions of each individual subsystem and the way that they work together to establish a robust and local PKI is described in this chapter.

2.1. A review of Certificate System subsystems

Red Hat Certificate System provides five different subsystems, each focusing on different aspects of a PKI deployment:

- A certificate authority called Certificate Manager. The CA is the core of the PKI; it issues and revokes all certificates. The Certificate Manager is also the core of the Certificate System. By establishing a security domain of trusted subsystems, it establishes and manages relationships between the other subsystems.

A key recovery authority (KRA). Certificates are created based on a specific and unique key pair. If a private key is ever lost, then the data which that key was used to access (such as encrypted emails) is also lost because it is inaccessible. The KRA stores key pairs, so that a new, identical certificate can be generated based on recovered keys, and all of the encrypted data can be accessed even after a private key is lost or damaged.

NoteIn previous versions of Certificate System, KRA was also referred to as the data recovery manager (DRM). Some code, configuration file entries, web panels, and other resources might still use the term DRM instead of KRA.

- An online certificate status protocol (OCSP) responder. The OCSP verifies whether a certificate is valid and not expired. This function can also be done by the CA, which has an internal OCSP service, but using an external OCSP responder lowers the load of the issuing CA.

- A token key service (TKS). The TKS derives keys based on the token CCID, private information, and a defined algorithm. These derived keys are used by the TPS to format tokens and enroll certificates on the token.

- A token processing system (TPS). The TPS interacts directly with external tokens, like smart cards, and manages the keys and certificates on those tokens through a local client, the Enterprise Security Client (ESC). The ESC contacts the TPS when there is a token operation, and the TPS interacts with the CA, KRA, or TKS, as required, then send the information back to the token by way of the Enterprise Security Client.

Even with all possible subsystems installed, the core of the Certificate System is still the CA (or CAs), since they ultimately process all certificate-related requests. The other subsystems connect to the CA or CAs likes spokes in a wheel. These subsystems work together, in tandem, to create a public key infrastructure (PKI). Depending on what subsystems are installed, a PKI can function in one (or both) of two ways:

- A token management system or TMS environment, which manages smart cards. This requires a CA, TKS, and TPS, with an optional KRA for server-side key generation.

- A traditional non token management system or non-TMS environment, which manages certificates used in an environment other than smart cards, usually in software databases. At a minimum, a non-TMS requires only a CA, but a non-TMS environment can use OCSP responders and KRA instances as well.

2.2. Overview of Certificate System subsystems

2.2.2. Instance installation prerequisites

2.2.2.1. Directory Server instance availability

Prior to installation of a Certificate System instance, a local or remote Red Hat Directory Server LDAP instance must be available. For instructions on installing Red Hat Directory Server, see the Red Hat Directory Server Installation Guide.

2.2.2.2. PKI packages

Red Hat Certificate System is composed of packages listed below:

- redhat-pki

- redhat-pki-base

- #redhat-pki-java

- #redhat-pki-javadoc

- python3-redhat-pki

- redhat-pki-tools

- redhat-pki-server

- redhat-pki-theme

- redhat-pki-ca

- redhat-pki-kra

- redhat-pki-ocsp

- redhat-pki-tks

- redhat-pki-tps

- redhat-pki-acme

- redhat-pki-est

- redhat-pki-console

- redhat-pki-console-theme

To install these packages, you must attach a Red Hat Certificate System subscription pool and enable the RHCS repository. For more information, see Section 6.3.2.3, “Attaching a Red Hat subscription and enabling the Certificate System package repository”.

Use a Red Hat Enterprise Linux 8 system (optionally, use one that has been configured with a supported Hardware Security Module listed in Chapter 4, Supported platforms), and make sure that all packages are up to date before installing Red Hat Certificate System.

To install all Certificate System packages (with the exception of pki-javadoc), use dnf to install the redhat-pki metapackage:

dnf install redhat-pki

# dnf install redhat-pkiAlternatively, you can install one or more of the top level PKI subsystem packages as required; see the list above for exact package names. If you use this approach, make sure to also install the redhat-pki-server-theme package, and optionally redhat-pki-console-theme and pki-console to use the PKI Console.

Finally, developers and administrators may also want to install the JSS and PKI javadocs (the jss-javadoc and pki-javadoc).

The jss-javadoc package requires you to enable the Server-Optional repository in Subscription Manager.

2.2.2.3. Instance installation and configuration

The pkispawn command line tool is used to install and configure a new PKI instance. It eliminates the need for separate installation and configuration steps, and may be run either interactively, as a batch process, or a combination of both (batch process with prompts for passwords). The utility does not provide a way to install or configure the browser-based graphical interface. For details on how to use pkispawn, see Installing RHCS using the pkispawn utility.

2.2.2.4. Instance removal

To remove an existing PKI instance, use the pkidestroy command. It can be run interactively or as a batch process. Use pkidestroy -h to display detailed usage information on the command line.

The pkidestroy command reads in a PKI subsystem deployment configuration file which was stored when the subsystem was created (/var/lib/pki/instance_name/<subsystem>/registry/<subsystem>/deployment.cfg), uses the read-in file in order to remove the PKI subsystem, and then removes the PKI instance if it contains no additional subsystems. See the pkidestroy man page for more information.

An interactive removal procedure using pkidestroy may look similar to the following:

A non-interactive removal procedure may look similar to the following example:

Key pairs are not deleted when a hardware token or a hardware security module (HSM) is used because you can have clone instances. Key pairs are only deleted when a soft token is used.

This is important because you can easily recreate instances and fill up a HSM memory without realizing the tokens are left in the HSM.

In this case, your certutil command output can look similar to the following example, using an environment variable $nssdb to point to a local NSS DB already initialized to reach to the HSM, and different from the PKI’s NSS DBs:

Destroy an instance, for example:

pkidestroy -v -i 2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1 -s CA 2>&1 | tee ~/pkidestroy.2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1.out.1.txt

# pkidestroy -v -i 2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1 -s CA 2>&1 | tee ~/pkidestroy.2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1.out.1.txtVerify that the instance has been deleted, for example:

pki-server instance-find

pki-server instance-findVerify the private keys from the deleted PKI instance till exist on the hardware token:

If you really need to delete those private keys, either use the certutil -F commands or the manufacturer tool, for example Luna Client cmu list and cmu delete with some options.

Following is a certutil example, with an already initialized NSS db directory:

certutil -F -d ${nssdb} -f ${nssdb}/hsm.password.txt -h thalesLunaDEV -n "thalesLunaDEV:auditSigningCert cert-2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1 CA"

certutil -F -d ${nssdb} -f ${nssdb}/hsm.password.txt -h thalesLunaDEV -n "thalesLunaDEV:Server-Cert cert-2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1 CA"

certutil -F -d ${nssdb} -f ${nssdb}/hsm.password.txt -h thalesLunaDEV -n "thalesLunaDEV:subsystemCert cert-2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1 CA"

certutil -F -d ${nssdb} -f ${nssdb}/hsm.password.txt -h thalesLunaDEV -n "thalesLunaDEV:ocspSigningCert cert-2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1 CA"

certutil -F -d ${nssdb} -f ${nssdb}/hsm.password.txt -h thalesLunaDEV -n "thalesLunaDEV:caSigningCert cert-2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1 CA"

certutil -F -d ${nssdb} -f ${nssdb}/hsm.password.txt -h thalesLunaDEV -n "thalesLunaDEV:auditSigningCert cert-2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1 CA"

certutil -F -d ${nssdb} -f ${nssdb}/hsm.password.txt -h thalesLunaDEV -n "thalesLunaDEV:Server-Cert cert-2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1 CA"

certutil -F -d ${nssdb} -f ${nssdb}/hsm.password.txt -h thalesLunaDEV -n "thalesLunaDEV:subsystemCert cert-2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1 CA"

certutil -F -d ${nssdb} -f ${nssdb}/hsm.password.txt -h thalesLunaDEV -n "thalesLunaDEV:ocspSigningCert cert-2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1 CA"

certutil -F -d ${nssdb} -f ${nssdb}/hsm.password.txt -h thalesLunaDEV -n "thalesLunaDEV:caSigningCert cert-2023-10-03-0139-10.4-rootca1 CA"Optional. Delete the system trust certificate or issuer or trust chain associated with a removed CA signing cert if there was one, for example:

2.2.3. Execution management (systemctl)

2.2.3.1. Starting, stopping, restarting, and obtaining status

Red Hat Certificate System subsystem instances can be stopped and started using the systemctl execution management system tool on Red Hat Enterprise Linux 8:

systemctl start <unit-file>@instance_name.service

# systemctl start <unit-file>@instance_name.servicesystemctl status <unit-file>@instance_name.service

# systemctl status <unit-file>@instance_name.servicesystemctl stop <unit-file>@instance_name.service

# systemctl stop <unit-file>@instance_name.servicesystemctl restart <unit-file>@instance_name.service

# systemctl restart <unit-file>@instance_name.service<unit-file> has one of the following values:

pki-tomcatd With watchdog disabled pki-tomcatd-nuxwdog With watchdog enabled

pki-tomcatd With watchdog disabled

pki-tomcatd-nuxwdog With watchdog enabled

For more details on the watchdog service, refer to the Section 2.3.9, “Passwords and watchdog (nuxwdog)” and Using the Certificate System Watchdog Service sections in the Red Hat Certificate System Administration Guide.

In RHCS 10, these systemctl actions support the pki-server alias: pki-server <command> subsystem_instance_name is the alias for systemctl <command> pki-tomcatd@<instance>.service.

2.2.3.2. Starting the instance automatically

The systemctl utility in Red Hat Enterprise Linux manages the automatic startup and shutdown settings for each process on the server. This means that when a system reboots, some services can be automatically restarted. System unit files control service startup to ensure that services are started in the correct order. The systemd service and systemctl utility are described in the Configuring basic system settings guide for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 8.

Certificate System instances can be managed by systemctl, so this utility can set whether to restart instances automatically. After a Certificate System instance is created, it is enabled on boot. This can be changed by using systemctl:

systemctl disable pki-tomcatd@instance_name.service

# systemctl disable pki-tomcatd@instance_name.serviceTo re-enable the instance:

systemctl enable pki-tomcatd@instance_name.service

# systemctl enable pki-tomcatd@instance_name.service

The systemctl enable and systemctl disable commands do not immediately start or stop Certificate System.

2.2.4. Process management (pki-server)

2.2.4.1. The pki-server command line tool

The primary process management tool for Red Hat Certificate System is pki-server. Use the pki-server --help command and see the pki-server man page for usage information.

The pki-server command-line interface (CLI) manages local server instances (for example server configuration or system certificates). Invoke the CLI as follows:

pki-server [CLI options] <command> [command parameters]

$ pki-server [CLI options] <command> [command parameters]The CLI uses the configuration files and NSS database of the server instance, therefore the CLI does not require any prior initialization. Since the CLI accesses the files directly, it can only be executed by the root user, and it does not require client certificate. Also, the CLI can run regardless of the status of the server; it does not require a running server.

The CLI supports a number of commands organized in a hierarchical structure. To list the top-level commands, execute the CLI without any additional commands or parameters:

pki-server

$ pki-serverSome commands have subcommands. To list them, execute the CLI with the command name and no additional options. For example:

pki-server ca pki-server ca-audit

$ pki-server ca

$ pki-server ca-auditTo view command usage information, use the --help option:

pki-server --help pki-server ca-audit-event-find --help

$ pki-server --help

$ pki-server ca-audit-event-find --help2.2.4.2. Enabling and disabling an installed subsystem using pki-server

To enable or disable an installed subsystem, use the pki-server utility.

pki-server subsystem-disable -i instance_id subsystem_id

# pki-server subsystem-disable -i instance_id subsystem_idpki-server subsystem-enable -i instance_id subsystem_id

# pki-server subsystem-enable -i instance_id subsystem_id

Replace subsystem_id with a valid subsystem identifier: ca, kra, tks, ocsp, or tps.

One instance can have only one of each type of subsystem.

For example, to disable the OCSP subsystem on an instance named pki-tomcat:

pki-server subsystem-disable -i pki-tomcat ocsp

# pki-server subsystem-disable -i pki-tomcat ocspTo list the installed subsystems for an instance:

pki-server subsystem-find -i instance_id

# pki-server subsystem-find -i instance_idTo show the status of a particular subsystem:

pki-server subsystem-find -i instance_id subsystem_id

# pki-server subsystem-find -i instance_id subsystem_id2.2.4.3. Finding the subsystem web services URLs

The CA, KRA, OCSP, TKS, and TPS subsystems have web services pages for agents, as well as regular users and administrators, when appropriate. These web services can be accessed by opening the URL to the subsystem host over the subsystem’s secure end user’s port. For example, for the CA:

https://server.example.com:8443/ca/services

https://server.example.com:8443/ca/servicesTo get a complete list of all of the interfaces, URLs, and ports for an instance, check the status of the service. For example:

pki-server status <instance_name>

pki-server status <instance_name>The main web services page for each subsystem has a list of available services pages; these are summarized in the below table. To access any service specifically, access the appropriate port and append the appropriate directory to the URL. For example, to access the CA’s end entities (regular users) web services:

https://server.example.com:8443/ca/ee/ca

https://server.example.com:8443/ca/ee/caIf DNS is not configured, then an IPv4 or IPv6 address can be used to connect to the services pages. For example:

https://192.0.2.1:8443/ca/services https://[2001:DB8::1111]:8443/ca/services

https://192.0.2.1:8443/ca/services

https://[2001:DB8::1111]:8443/ca/servicesAnyone can access the end user pages for a subsystem. However, accessing agent or admin web services pages requires that an agent or administrator certificate be issued and installed in the web browser. Otherwise, authentication to the web services fails.

| Port | Used for SSL/TLS | Used for Client AuthenticationServices with a client authentication value of No can be reconfigured to require client authentication. Services which do not have either a Yes or No value cannot be configured to use client authentication. | Web Services | Web Service Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| 8080 | No | End Entities | |

| ca/ee/ca | 8443 | Yes | No | End Entities |

| ca/ee/ca | 8443 | Yes | Yes | Agents |

| ca/agent/ca | 8443 | Yes | No | Services |

| ca/services | 8443 | Yes | No | Console |

| pkiconsole https://host:port/ca |

| 8080 | No | |

| End Entities | kra/ee/kra | 8443 | Yes | No |

| End Entities | kra/ee/kra | 8443 | Yes | Yes |

| Agents | kra/agent/kra | 8443 | Yes | No |

| Services | kra/services | 8443 | Yes | No |

| Console | pkiconsole https://host:port/kra |

| 8080 | No |

| End Entities | ocsp/ee/ocsp | 8443 | Yes | |

| No | End Entities | ocsp/ee/ocsp | 8443 | Yes |

| Yes | Agents | ocsp/agent/ocsp | 8443 | Yes |

| No | Services | ocsp/services | 8443 | Yes |

| No | Console | pkiconsole https://host:port/ocsp |

| 8080 |

| No | End Entities | tks/ee/tks | 8443 | |

| Yes | No | End Entities | tks/ee/tks | 8443 |

| Yes | Yes | Agents | tks/agent/tks | 8443 |

| Yes | No | Services | tks/services | 8443 |

| Yes | No | Console | pkiconsole https://host:port/tks |

|

| 8080 | No | Unsecure Services | tps/tps | |

| 8443 | Yes | Secure Services | tps/tps | |

| 8080 | No | Enterprise Security Client Phone Home | tps/phoneHome | |

| 8443 | Yes | Enterprise Security Client Phone Home | tps/phoneHome | |

| 8443 | Yes | Yes | Admin, Agent, and Operator Services | tps/ui |

2.2.4.4. Starting the Certificate System console

This console is being deprecated.

The CA, KRA, OCSP, and TKS subsystems have a Java interface which can be accessed to perform administrative functions. For the KRA, OCSP, and TKS, this includes very basic tasks like configuring logging and managing users and groups. For the CA, this includes other configuration settings such as creating certificate profiles and configuring publishing.

The Console is opened by connecting to the subsystem instance over its SSL/TLS port using the pkiconsole utility. This utility uses the format:

pkiconsole https://server.example.com:admin_port/subsystem_type

pkiconsole https://server.example.com:admin_port/subsystem_type

The subsystem_type can be ca, kra, ocsp, or tks. For example, this opens the KRA console:

pkiconsole https://server.example.com:8443/kra

pkiconsole https://server.example.com:8443/kraIf DNS is not configured, then an IPv4 or IPv6 address can be used to connect to the console. For example:

https://192.0.2.1:8443/ca https://[2001:DB8::1111]:8443/ca

https://192.0.2.1:8443/ca

https://[2001:DB8::1111]:8443/ca2.3. Certificate System architecture overview

Although each provides a different service, all Red Hat Certificate System subsystems (CA, KRA, OCSP, TKS, TPS) share a common architecture. The following architectural diagram shows the common architecture shared by all of these subsystems.

2.3.1. Java application server

Java application server is a Java framework to run server applications. The Certificate System is designed to run within a Java application server. Currently the only Java application server supported is Tomcat. Support for other application servers may be added in the future.

Each Certificate System instance is a Tomcat server instance. Each Certificate System subsystem (such as CA or KRA) is deployed as a web application in Tomcat. The web application configuration is stored in a web.xml file, which is defined in Java Servlet 3.1 specification. See https://www.jcp.org/en/jsr/detail?id=340 for details.

The Certificate System configuration itself is stored in CS.cfg.

See Section 2.3.14, “Instance layout” for the actual locations of these files.

2.3.2. Java security manager

Java services have the option of having a Security Manager which defines unsafe and safe operations for applications to perform. When the subsystems are installed, they have the Security Manager enabled automatically, meaning each Tomcat instance starts with the Security Manager running.

The Security Manager is disabled if the instance is created by running pkispawn and using an override configuration file which specifies the pki_security_manager=false option under its own Tomcat section.

The Security Manager can be disabled from an installed instance using the following procedure:

First stop the instance:

pki-server stop instance_name

# pki-server stop instance_nameCopy to Clipboard Copied! Toggle word wrap Toggle overflow or (if using the

nuxwdogwatchdog)systemctl stop pki-tomcatd-nuxwdog@instance_name.service

# systemctl stop pki-tomcatd-nuxwdog@instance_name.serviceCopy to Clipboard Copied! Toggle word wrap Toggle overflow -

Open the

/etc/sysconfig/instance_namefile, and setSECURITY_MANAGER="false" After saving, restart the instance:

pki-server start instance_name

# pki-server start instance_nameCopy to Clipboard Copied! Toggle word wrap Toggle overflow or (if using the

nuxwdogwatchdog)systemctl start pki-tomcatd-nuxwdog@instance_name.service

# systemctl start pki-tomcatd-nuxwdog@instance_name.serviceCopy to Clipboard Copied! Toggle word wrap Toggle overflow

When you start or restart an instance, a Java security policy is constructed or reconstructed from the following files:

/usr/share/pki/server/conf/catalina.policy /usr/share/tomcat/conf/catalina.policy /var/lib/pki/$PKI_INSTANCE_NAME/conf/pki.policy /var/lib/pki/$PKI_INSTANCE_NAME/conf/custom.policy

/usr/share/pki/server/conf/catalina.policy

/usr/share/tomcat/conf/catalina.policy

/var/lib/pki/$PKI_INSTANCE_NAME/conf/pki.policy

/var/lib/pki/$PKI_INSTANCE_NAME/conf/custom.policy

Then, it is saved into /var/lib/pki/ instance_name/conf/catalina.policy.

2.3.3. Interfaces

2.3.3.1. Servlet interface

Each subsystem contains interfaces allowing interaction with various portions of the subsystem. All subsystems share a common administrative interface and have an agent interface that allows for agents to perform the tasks assigned to them. A CA Subsystem has an end-entity interface that allows end-entities to enroll in the PKI. An OCSP Responder subsystem has an end-entity interface allowing end-entities and applications to check for current certificate revocation status. Finally, a TPS has an operator interface.

While the application server provides the connection entry points, Certificate System completes the interfaces by providing the servlets specific to each interface.

The servlets for each subsystem are defined in the corresponding web.xml file. The same file also defines the URL of each servlet and the security requirements to access the servlets. See Section 2.3.1, “Java application server” for more information.

2.3.3.2. Administrative interface

The agent interface provides Java servlets to process HTML form submissions coming from the agent entry point. Based on the information given in each form submission, the agent servlets allow agents to perform agent tasks, such as editing and approving requests for certificate approval, certificate renewal, and certificate revocation, approving certificate profiles. The agent interfaces for a KRA subsystem, or a TKS subsystem, or an OCSP Responder are specific to the subsystems.

In the non-TMS setup, the agent interface is also used for inter-CIMC boundary communication for the CA-to-KRA trusted connection. This connection is protected by SSL client-authentication and differentiated by separate trusted roles called Trusted Managers. Like the agent role, the Trusted Managers (pseudo-users created for inter-CIMC boundary connection only) are required to be SSL client-authenticated. However, unlike the agent role, they are not offered any agent capability.

In the TMS setup, inter-CIMC boundary communication goes from TPS-to-CA, TPS-to-KRA, and TPS-to-TKS.

2.3.3.3. End-entity interface

For the CA subsystem, the end-entity interface provides Java servlets to process HTML form submissions coming from the end-entity entry point. Based on the information received from the form submissions, the end-entity servlets allow end-entities to enroll, renew certificates, revoke their own certificates, and pick up issued certificates. The OCSP Responder subsystem’s End-Entity interface provides Java servlets to accept and process OCSP requests. The KRA, TKS, and TPS subsystems do not offer any End-Entity services.

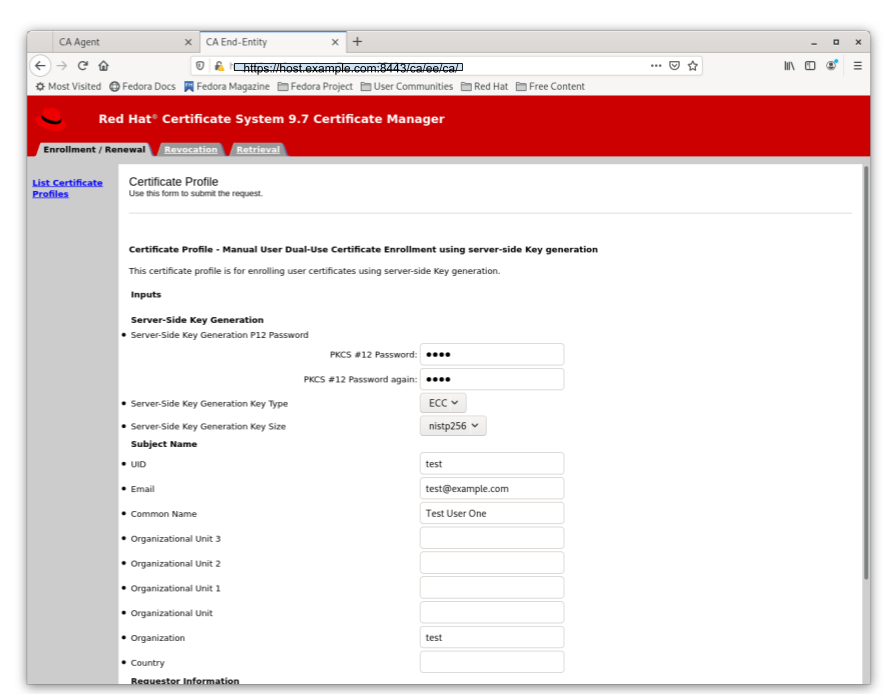

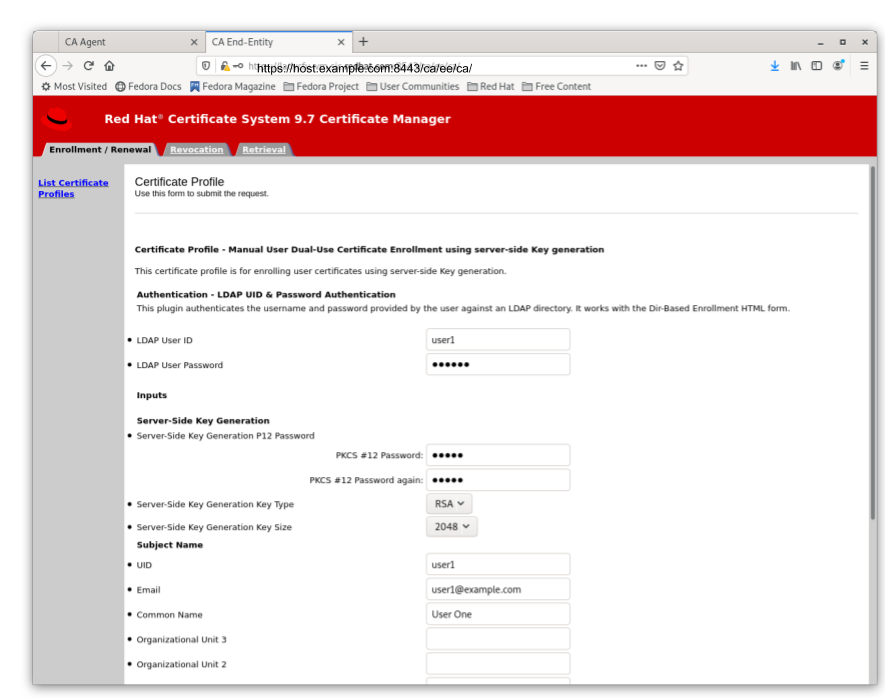

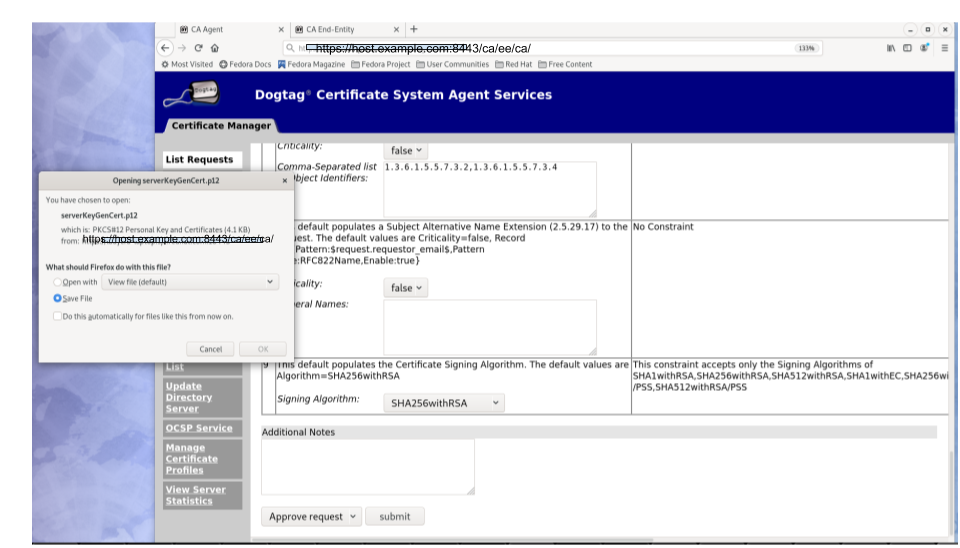

2.3.3.4. Operator interface